The Cholesterol Cult & Heart Mafia: How the process of science evolves into The Science™ of public policy

"Narrative selection" is a process by which scientific ideas evolve into public dogmas.

A recent online interaction interaction with Elon Musk illustrates a common belief about human health which has been endemic to the Western world since the mid-1900s:

Musk: Wow, steak & eggs with coffee in the morning really feels like a powerup!

Some guy: Sounds like a heart attack in the long-term.

This response comes from a belief that higher cholesterol levels entail higher cardiovascular disease risk. Whether he realizes it or not, the gentleman above is espousing belief in the “diet-heart hypothesis”: dietary saturated fat and cholesterol increase blood cholesterol, driving heart disease. Hence the belief, steak & eggs = heart attack.

Knowingly or not, Bill Gates is another proponent of the diet-heart-hypothesis. It shapes his evaluation of what constitutes a healthy diet and steers his decision making about where to place investments. Here’s something he said about diet and human health:

Bill: Of all the categories, the one that has gone better than I would have expected five years ago is this work to make what’s called artificial meat. And so you have people like Impossible or Beyond Meat, both of which I invested in.

Some guy: Do you eat it as well? Do you like it?

Bill: Absolutely. You can go to Burger King and buy the Impossible Burger.

Some guy: Is it healthier for you, or just healthier for the atmosphere?

Bill: It’s slightly healthier for you in terms of less cholesterol.

I have no interest in wading into the economics or ethics here. Our focus will be on Mr. Gates’ health claims about cholesterol and plant-based meats, the psychology from which they arise, and the social mechanisms that can produce an illusion of consensus in science.

What does Bill mean when he says that plant-based artificial meat is, “healthier for you in terms of less cholesterol”? He means that it contains less cholesterol than animal meat and will therefore reduce your cardiovascular disease risk. Standard thinking among devotees of the diet-heart thesis.

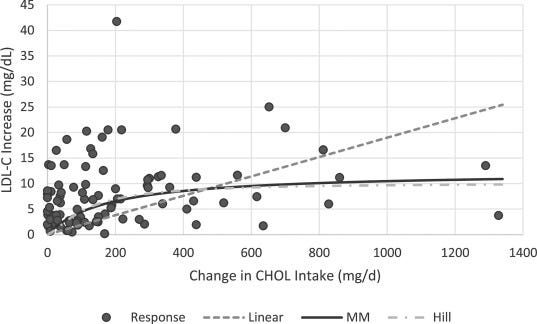

But there’s a problem: dietary cholesterol intake has only a modest impact on cholesterol levels. There’s also a “diminishing returns” effect—the higher the baseline level of dietary cholesterol intake, the less serum cholesterol rises in response to consuming more. This is likely due to negative feedback mechanisms that reduce cholesterol synthesis within the body in response to dietary intake. The fact that our bodies synthesize cholesterol de novo and negative feedback mechanisms exist to regulate overall levels tells us something: the body “wants” cholesterol levels to be neither too high nor too low. (More on that, later).

Like most people, Mr. Gates doesn’t seem to know these things. Saturated fat intake can increase serum cholesterol, but the plant-based meats Bill invested in have similar saturated fat levels to animal meat. Artificial plant meats do have lower cholesterol content than real meat, which is why Bill said what he said. Like I once did, Gates appears to believe in the diet-heart hypothesis without knowing much about the relevant biology.

Why would somebody believe in a biological idea without a solid grasp of the underlying biology? Especially someone with a reputation as smart, evidence-based, and pro-science? Perhaps the answer is that, like me, Mr. Gates did not arrive at his beliefs regarding cholesterol from thorough examination of the relevant science. Perhaps, like me, his beliefs were given to him by fiat.

Mr. Gates and Mr. Musk represent two types of people with respect to the diet-heart hypothesis. The first type believes in it implicitly, likely without ever having held a different viewpoint: dietary saturated fat and cholesterol drive heart disease—therefore: steak and eggs bad, plant-based meat good. The second type represents a smaller slice of people who once endorsed the diet-heart thesis, but no longer do (they may also be totally unaware of this). I’ve been both types. As a child, I believed it was healthy to minimize saturated fat intake and replace cow’s milk with soy milk. Today, I eat lots of eggs, grass-fed beef, and butter.

How and why do these beliefs arise and evolve in different ways, in different people?

We’ll be delving into some of the biology and history relevant to the diet-heart hypothesis, but only insofar as it helps support my effort to analyze how science-based beliefs form and spread in modern society. More specifically, we’ll look at the ways in which scientific ideas can spread by non-scientific social transmission mechanisms. Doing this will reveal how many “evidence-based” claims are little more than religious beliefs masquerading as science in order to dictate how people’s behavior should be managed. Ultimately, this is done to promote social structures that secure the positions of high-status people within status hierarchies.

Fiat Science: How the public assimilates scientific ideas

As an old Millennial born in the late 1980s, I grew up at the height of the diet-heart hypothesis’ potent influence on American society. The low-fat craze. Plenty of grains. I Can’t Believe It’s Not Butter! The focus on low-fat dieting distracted people from how much added sugar was in their “heart healthy” cereal. The demonization of saturated fat caused us to feel good about spreading fake butter loaded with industrial trans fats onto our white bread. Ideas spread when they make people feel good about themselves.

Dietary guidelines are set by government institutions, made in consultation with credentialed experts. The official guidelines were distilled into the food pyramid, diligently uploaded to the minds of American school children by the public school system. People did heed the guidelines, as reflected in food consumption treads seen in the data (dissected more thoroughly, here). In the 1990s of my childhood, everyone was preaching the low cholesterol gospel.

I wish we could blame Fabio, but every adult who my young mind naturally viewed as an authority said the same things, for my entire childhood and adolescence. Today, many of those adults are either dead, obese, or shooting up Ozempic. Those living probably still believe that eating cholesterol is unhealthy. We received the ideas by fiat—credentialed experts told us it was The Science™.

It doesn’t feel like a cult while you’re in it. But I’m getting ahead of myself.

As an adolescent I remember explaining to my mother that Silk was healthier than milk. Like most teens, I knew it without ever reflecting on the origins of my belief, which did not arise from careful study of physiology. At the time, I had no interest in or knowledge of human metabolism. But believing the right thing made me feel good. It also felt good telling other people what to believe. I was a vector for a meme.

Like a cold, my belief was something I caught, something in the air—or rather, on the television. Just as we don’t choose to be infected by viruses, we don’t choose to be infected by memes. We catch them from the environment.

It was only after years of study that I renounced my faith in the tenets of the diet-heart creed. In that time, the same set of beliefs about the negative health effects of saturated fat and cholesterol continued spreading globally. I may have lost faith in the diet-heart hypothesis, but Bill Gates has not. Your family doctor almost certainly believes in it, which is why cholesterol-lowering drugs (statins) are among the most-prescribed pharmaceuticals ever. In fact, there is wide consensus among medical experts—people with stellar credentials and high-level positions in government agencies, global health organizations, and hospitals—that the diet-heart thesis is correct. Should we not trust the experts, especially when there’s consensus among them?

The diet-heart "consensus” is illusory. I’m certainly not the only one who has lost faith. To understand what’s going on here, we have to do two things:

See plainly that the diet-heart hypothesis is anything but settled science.

Understand how scientific ideas become dominant within institutions, enshrined in public policy, and exported to the masses in narrative form.

Doing this will reveal that scientific ideas do not spread solely based on the quality of supporting evidence, and that expert consensus is not merely a function of dispassionate truth-seeking. Our ideas serve social functions and spread based on their social utility. As social animals, our lot in life is determined by our position in social status hierarchies. We live in groups. Some of these are informal and form through spontaneous interaction, such as your circle of personal friends. Others are formally structured and explicitly designed to assemble and disseminate ideas into coherent narratives, such as institutions. The purpose of such narratives is to organize human group behavior

In the Darwinian battle of ideas, a meme will spread insofar as it can be integrated into a social narrative that justifies the growth and expansion of institutions. Institutions are designed to communicate ideas to people en masse, and are composed of humans—people who adopt and promote ideas that justify their social goals (e.g. career advancement). I’ve called this process, “narrative selection,” by analogy with natural selection.

The truth value of an idea is just one of many things that determine an idea’s social utility. As Mark Twain said, “A lie can travel halfway around the world while the truth is still putting on its shoes.” People routinely adopt and spread ideas for reasons other than truth. The word politics comes to mind.

Like most people, my implicit childhood belief in the diet-heart thesis came to me by fiat—I was told to believe those things by elements of culture, including corporate advertisements and who I perceived to be an expert. One way this occurs at scale is through an official (government) public education campaigns, built from the perception of expert consensus within key institutions dictating public policy.

Illusion of Consensus: How institutions manufactured the diet-heart “consensus”

The saga of the diet-heart hypothesis, how it spread, and why it never rested on compelling evidence, has been covered in detail elsewhere. For a concise history, I recommend this paper. I’ve also discussed this topic with multiple physician-scientists on the podcast:

M&M #131: Dietary Fat, Cholesterol, Cardiovascular Health & Disease, Carbohydrates, Dietary Guidlines, Food Industry & Diet Research | Ronald Krauss, MD

M&M #135: History of Diet Trends & Medical Advice in the US, Fat & Cholesterol, Seed Oils, Processed Food, Ketogenic Diet, Can We Trust Public Health Institutions? | Orrin Devinsky, MD

M&M #140: Obesogens, Oxidative Stress, Dietary Sugars & Fats, Statins, Diabetes & the True Causes of Metabolic Dysfunction & Chronic Disease | Robert Lustig, MD

To repeat the diet-heart thesis: higher cholesterol levels are associated with higher rates of cardiovascular disease. When surgeons scoop plaque out of arteries, those plaques contain cholesterol. Saturated fat intake elevates serum cholesterol. Therefore, blood cholesterol is the main culprit in heart disease, and limiting saturated fat intake is the dietary solution.

Our society is ruled by consensus mechanisms. Elected officials are chosen by a majority consensus of voters. Public health policies and dietary guidelines are set by official institutions like the USDA, which constructs them by consultation with experts—people uniquely qualified to determine what is true, and communicate a reasonable consensus of the facts to policymakers. These experts are typically people with specific credentials granted to them by other institutions, such as universities. They are also humans, with the same self-interested social goals as anyone else.

Social crises increase the pressure to reach consensus

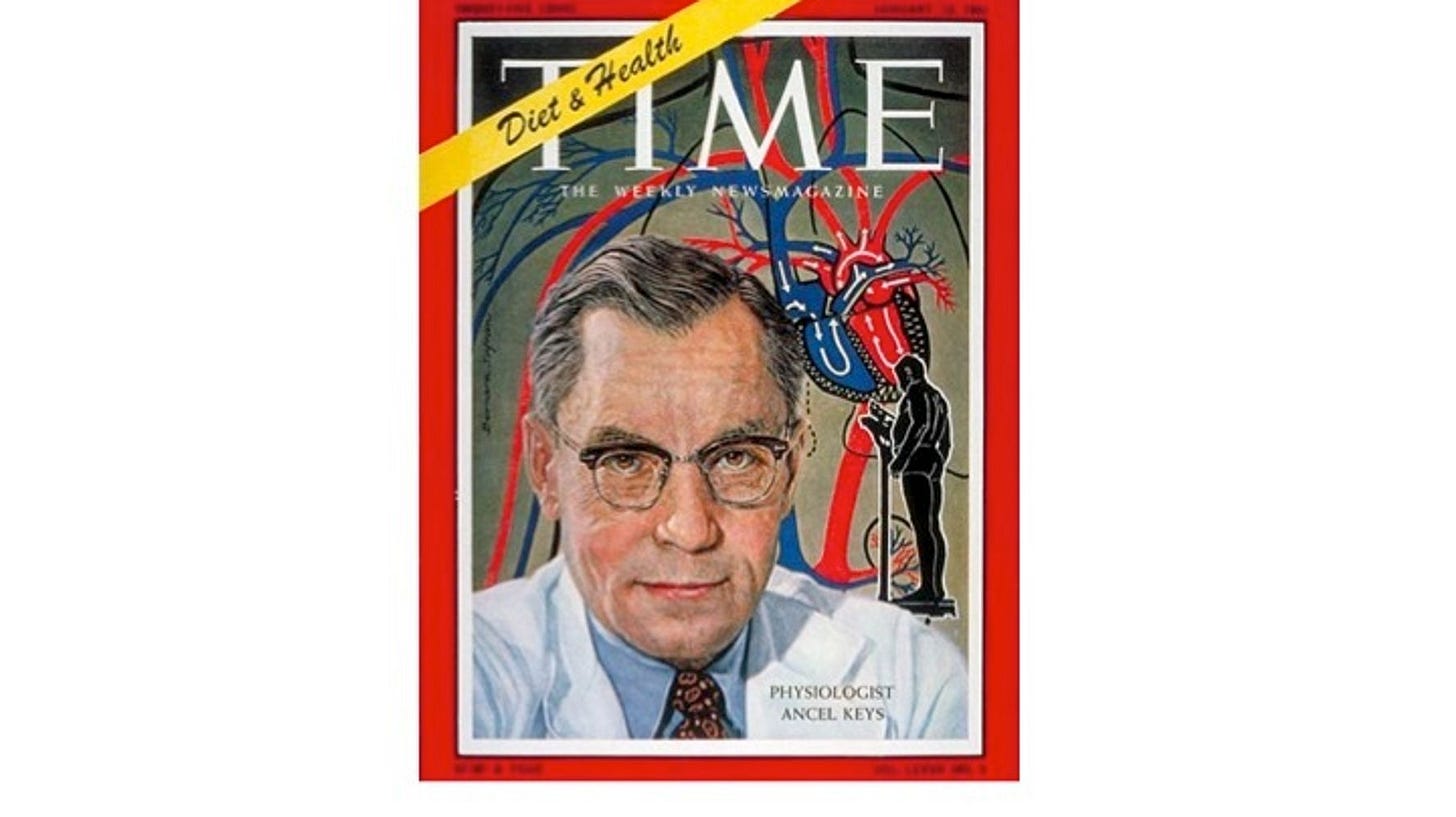

Since at least the 1950s, the diet-heart thesis has been the dominant narrative in medicine, promulgated to the masses by large institutions via public education campaigns. It was championed by the Dr. Ancel Keys in the mid-1900s. In a nutshell, his hypothesis spread due to the efforts of Keys and his supporters, who were able to get an out-sized amount of weight placed on the limited evidence they had to support it. Keys wasn’t just a hard-working researcher—he was socially successful, spreading his ideas via relationships with decision-makers in influential institutions.

A social crisis made the hasty adoption of Keys’ ideas possible: the US was in the midst of a cardiovascular disease epidemic, brought to the fore of public consciousness when President Eisenhower suffered a massive heart attack in 1955. A public health crisis creates intense pressure for policy solutions. For a high-profile national problem, those who are recognized as solving it will be granted much social status. Those working on the problem, like Dr. Keys, were highly motivated to provide a solution and receive recognition for it.

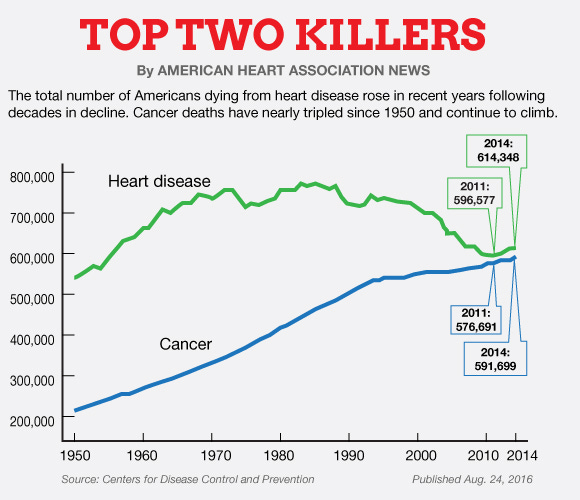

Here is a graph from the American Heart Association, showing deaths from heart disease and cancer over time:

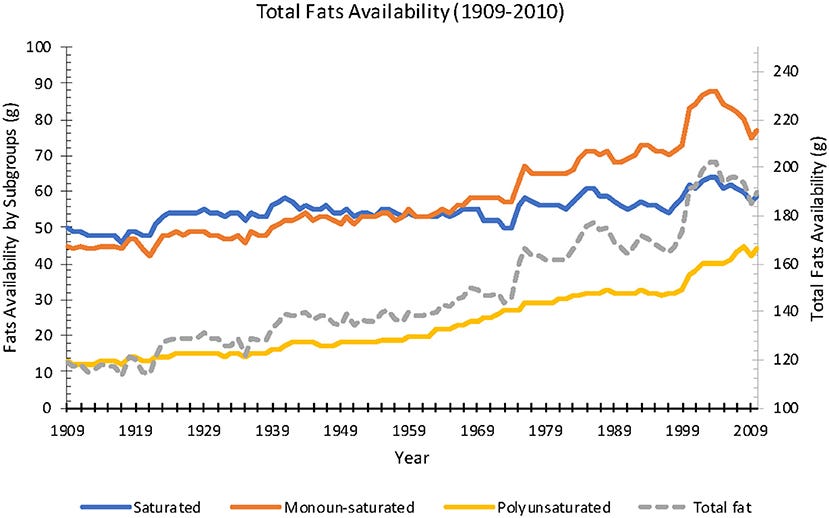

Notice that heart disease deaths were rising by 1950, peaked by 1990, then mostly declined. In contrast, cancer rates have steadily increased over the same time period (keep that result in the back of your mind). If high cholesterol driven by saturated fat intake is the major driver of heart disease, we’d expect to see correlated change in saturated fat consumption over this interval. Likewise, because polyunsaturated fats (PUFAs) from vegetable oils and other processed foods lower cholesterol, we would expect to see an inverse relationship with heart disease under the diet-heart hypothesis.

What do we observe?

Saturated fat consumption was actually flat, even declining somewhat, from 1940 into the 1970s. In contrast, PUFA consumption has almost continually been rising since the early 1900s. These high-level trends were driven largely by the replacement of animal-based fats (higher in saturated fat) with PUFA-rich vegetable (seed) oils starting in the 1940s. In other words, during the heart disease panic of the 1950s and 60s, when Keys’ ideas were adopted, saturated fat intake had already begun to be replaced by PUFAs.

PUFAs are deemed “heart healthy” by the AHA and other major institutions. Coincidentally, AHA was paid over $20 million in today’s dollars by Procter & Gamble, makers of the PUFA-rich seed oil Crisco, back in 1948. That was a few years before Eisenhower’s heart attack, when the heart disease crisis came into full public view. In 1961 AHA provided the recommendation to limit saturated fat intake, which has been called, “arguably the single-most influential nutrition policy ever published, as it came to be adopted first by the U.S. government, as official policy for all Americans, in 1980, and then by governments around the world as well as the World Health Organization.” Virtually all major health institutions coalesced around one narrative, ostensibly because a scientific consensus had formed.

Public health crises demand solutions now, not later. Policymakers want to implement expert-approved solutions ASAP—jobs, promotions, and credibility are on the line. The experts they consult may therefore be motivated to sell the best ideas they have as more iron-clad than they really are. Experts closely connected to the policymaking apparatus will be biased to prematurely coalesce around the most ascendent ideas suggesting an implementable policy solution, so that they may gain social status by association with the winning idea. The greater the social pressure, the greater the chance for an illusory consensus to emerge.

While Keys and others did amass evidence for their claims, this evidence had major shortcomings:

Much of it was correlational, lacking the ability to establish cause-and-effect relationships between dietary saturated fat and cholesterol with heart disease.

Animal research, causally showing that dietary cholesterol (a) spiked blood cholesterol, and (b) led to cardiovascular disease, was often done in species metabolically distinct from humans. For example, many early studies in this field used rabbits. As herbivores, rabbits respond to dietary cholesterol in radically different ways from meat-eating omnivores like humans. Their bodies did not evolve for cholesterol intake.

Many of the human epidemiological studies showing a correlation between dietary fat consumption and heart disease were either highly undersampled, not representative of the populations they drew from, or composed of cherry-picked data. The most infamous example is Keys’ “Seven Countries Study.” The observed associations often disappeared when more robust datasets were analyzed, and have been contradicted by larger, more robust analyses since.

Despite those shortcomings, Dr. Keys’ hypothesis gained favor. Weaknesses in the evidence were overlooked due to the immense social pressure surrounding the very public spotlight that had been placed on solving the problem. The evidence was viewed as good enough, given the pressure policymaking institutions were under to implement a solution.

Competition for social status distorts the “marketplace of ideas”

If you study the history of Ancel Keys, you see clearly that Keys was not just a prolific and hardworking researcher, he was also a charismatic and ambitious career man. Even in science, ideas do not rise and fall based solely on the strength of evidence. Their adoption is a function of both the supporting data and social factors, such as salesmanship. Like anyone else, scientists are motivated by fame and glory (social status). Keys knew how to sell his ideas, and to cultivate a social network connecting him to decision makers within powerful institutions.

Ideas do not exist as disembodied Platonic forms, competing with one another in a rational “marketplace of ideas.” Ideas exist in human minds, which are only partially rational and truth-seeking. Ideas spread between minds through social interaction, battling for dominance based on their utility in putting people on a desired trajectory within social status hierarchies. People want either more status or security in what they have, choosing to endorse and spread ideas accordingly.

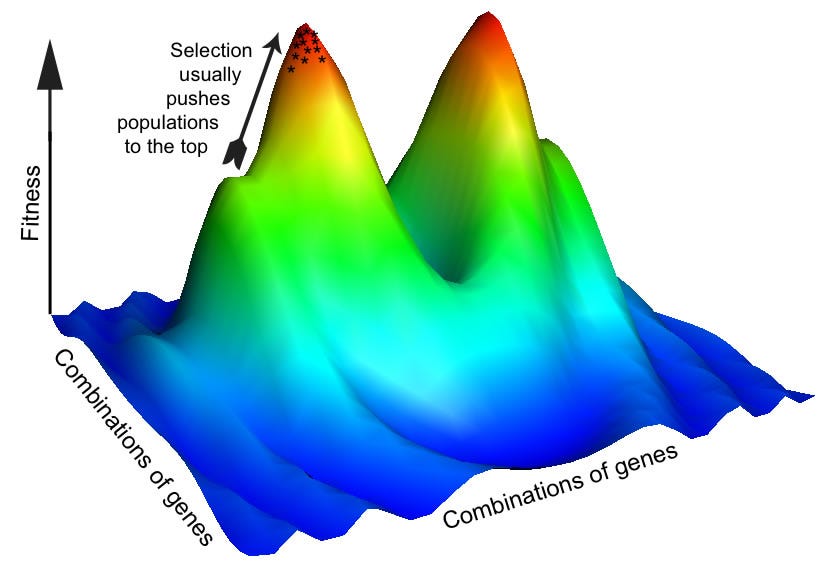

The marketplace of ideas is not flat, providing equal opportunity for all ideas to compete based on their ability to predict the external world. It’s a fitness landscape of hills and valleys. In genetic evolution, fitness landscapes visualize how adaptive different traits are within a given environment—hills represent high fitness, valleys low fitness. The physical environment determines the topology of this landscape.

In memetic evolution, a similar concept can be used, except that the fitness landscape corresponds to a highly dynamic social environment. The topology of the social fitness landscape isn’t limited solely by physical conditions, but by social rules set by the actors social groups are composed of. High-status individuals, especially those concentrated within prestigious institutions, have an out-sized ability to set social norms and constrain information flow between people. They can use their influence to bias peaks in the social fitness landscape toward their preferred ideas. Naturally, people prefer ideas that secure them high status within social hierarchies.

To give a sense of just how much social status was at stake with regard to the diet-heart hypothesis: Ancel Keys made the cover of Time Magazine, earning a reputation as a national hero for “solving” heart disease. This puts him in league with Jonas Salk in terms of public fame among scientists.

The stronger the competition for social status, the greater the incentive to cheat

The main thrust propelling Keys to scientific and public stardom (high social status) came from his Seven Countries Study. It was some time before anyone realized that, he had apparently cherry-picked the data. Dr. Robert Lustig explained this in M&M #140:

RL: Ancel Keys—he was a hero even appeared on the cover of Time. And now he is a villain, and has been appropriately vilified. He was the one who basically correlated saturated fat consumption with mortality due to cardiovascular disease back in the 1950s. However, when you look at the data, he cherry picked it. Okay? And all the countries that he picked in his Seven Countries Study, even though there were 22, he picked the seven that made his case.

NJ: Is it established fairly well that he intentionally cherry pick this data?

RL: Well, intent is complicated. I never asked him. I don't know that anyone ever asked him if he intended. But there were 22 countries. And when he published it, there were only seven. We have the data on the other 15 and they don't fit. So I don't know. You tell me. Did he or didn't he?

Based on the evidence put forth, the diet-heart hypothesis was transformed into public policy. The right people endorsed it, believing that a critical mass of experts had reached a reasonable consensus. It was a major factor driving the design of the food pyramid and the low-fat diet crazes of the late 1900s.

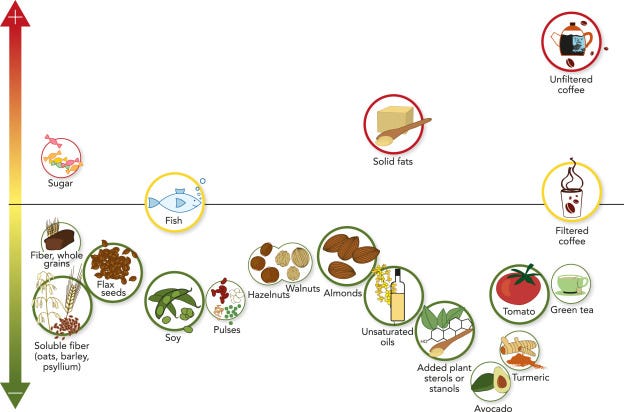

To this day, the American Heart Association and other prestigious institutions promote the idea that lower cholesterol is always “heart healthy,” and that one should swap saturated fat intake for polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs). It’s why you see cereal boxes containing ultra-processed grains with added sugar proudly advertising themselves as “AHA Certified.”

When hypotheses become policy, ideas become dogma.

The social conditions propelling Keys’ thesis forward were so strong that competing evidence was suppressed from publication, as was done for key experiments of the Framingham Heart Study. Conducted from the 1940s-1960s, researchers conducted as rigorous a study as could have been done at the time to test the diet-heart thesis. I spoke with Dr. Orrin Devinsky about this study on M&M #135, who provided a sense for the distorting effects the social hysteria around heart disease had on the research world:

In 1961, they published their first paper on risks factors—that’s where the term “risk factor” comes from—and that was the study that showed, especially men middle-aged or older who have total cholesterols over 260, had higher rates of cardiovascular disease and death. And no doubt, I think that’s true. What no one talks about is that that same Framingham Study, and many, many other studies since, have found that very low cholesterol levels have been associated with higher rates of cancer, accidental death, and suicide deaths.

Overall, even in Framingham for men whose cholesterol was under 160, total mortality was not terribly different than men whose cholesterol was over 260. But in 1960 is was heart disease, heart disease, heart disease. No one talked about nutrition and cancer. And when they eventually did they just lumped saturated fat with heart disease and said, “Well, it must be causing cancer, too. Because it’s got to, right? There’s more cancer now than there used to be, it’s gotta be saturated fat!”

In other words, even at the time, the commitment to the idea that high cholesterol = heart disease led people to overlook emerging evidence for the health risks of low cholesterol levels. Remember the trend in cancer rates, which have been on continuous rise? Low cholesterol is a factor, which suggests the possibility that our myopic focus on lowering cholesterol may be having unfortunate side effects.

By the time of the Framingham results, Keys’ diet-heart hypothesis was not just an ascendent idea, it was dogma. Traditionally, the word “dogma” is associated with religious beliefs. A telltale sign of dogma—and idea which is given by fiat and cannot be questioned—is the suppression of evidence contradicting it.

And that’s exactly what happened.

Results that directly contradicted Keys’ diet-heart thesis went unpublished, collecting dust for decades before seeing the light of day. Dr. Devinsky described this unsettling episode in medical history:

Just to show how politics get ugly: A very famous doctor in the Framingham Heart story, George Mann, who studied the Maasai, one of those populations where they eat milk, blood, and meat—very, very, very high saturated fat diets. Extraordinarily high fat diet and low heart disease rates. And he got lambasted. He became a persona non grata and eventually lost all of his funding.

As a doctor at Framingham, he did a nutritional study that went for four years, from 1956 to 1960. And in a cohort of like 2,000 people, he and a dietician went to the houses, interviewed homemakers about what they cooked, measured things, weighed things, and looked in great detail at what people consumed and then followed them and looked at what their heart disease rate was, mortality, etc. What they found was no correlation between how much saturated fat you ate and what your cholesterol was, nor any relationship between how much saturated fat you ate and your heart health.

What happened to that study? He was forbidden from publishing it. It exists as a supplement to the Framingham Study that you could not get at any medical library in the US. I was able to get a [copy] from the Framingham library, and amazingly it got published by a statistician who said, “I found this incredible study. It’s basically been buried. The data is immaculate. The study was beautifully performed, and I feel like it’s my duty to write this up. And he wrote it up.”

So, they did the best study they could do in the late 1950s, and because it didn’t agree with the dogma of Ancel Keys and his crew, they buried it.

A crushing example of how the illusion of consensus can emerge. If contradictory information is barred from publication, it looks like all the experts agree. If you’re a scientist working in such an environment, where going against dogma carries career risk, you may simply choose not to publish the results. Do you want to rock the boat, or get tenure?

One characteristic of religious cults is the rigidity of their ideas and severe penalties they impose on people who refuse to conform or try to leave. When cults recruit new members, they push them to sever ties with outsiders—they want to prevent any and all exposure to contradictory ideas, as this can destabilize the internal social status hierarchy from which cult leaders derive immense benefit. (Humans are animals, and it is no wonder that cults often function as harems for their leaders).

Anyways…

Who, exactly, buried the Framingham results? Who was preventing evidence that contradicted the diet-heart narrative from publicly emerging? Dr. Devinsky’s word choice was telling:

The “heart mafia”—the American Heart Association, the NIH. The National Health Service, I believe, paid for the Framingham Heart Study. Our tax dollars paid for the study. And they buried it. They would not allow it to come out.

Dr. Orrin Devinsky is as decorated and mainstream as one can be. He’s been a board-certified neurologist and professor at NYU for decades, serving as Director of the Comprehensive Epilepsy Center. This is not a fringe character. Heart mafia. Those are his words, which gives an indication of the nature of the social forces at work behind the scenes—forces that decide which ideas are allowed to influence public policy, and which are not.

The heartbreaking case of Dr. Mann is one telling story, part of a larger pattern that played out until the rest of the 20th century. As described elsewhere:

Reviews and books critical of the diet-heart hypothesis were not unknown in the 1960s and 1970s, including a publication by a former editor of the Journal of the American Heart Association and articles by other prominent scientists. They argued that the hypothesis was not supported by the available data and was contradicted by numerous observations. Over time, however, these critics were effectively marginalized and silenced

[NJ: Notice that a contrary publication came from a former editor of the AHA. One wonders: why did they publish only after leaving the AHA?]

As with a literal, Italian-style criminal mafia, it’s impossible for outsiders to know exactly what goes on behind the scenes. But we know how mafias operate: they use social force to extract unearned rents and ensure conformity to their demands. The threat of force is used to extort individuals, even when they do not freely opt-in to the arrangement—open a deli in the wrong neighborhood in Jersey, and you gotta pay up. Or else.

Dr. George Mann didn’t have his kneecaps busted with a crowbar, but he was disappeared. For a scientist, that’s what having your funding pulled amounts to. “He became a persona non grata and eventually lost all of his funding,” as Dr. Devinsky put it. Whether it’s government agencies like the NIH or “nonprofits” like the AHA (annual revenue: $1.2 billion), institutions providing funding to scientists can steer research in certain directions by selectively pulling funding.

Funding agencies offer guidelines on the general lines of inquiry they want to see explored, but they don’t explicitly tell people, “The data better come out this way, or else!” They can, however, stop funding individual researchers if the results undermine conclusions deemed untouchable by made men.

Notice again the analogy with evolution by natural selection: the social environment (funding agencies) selectively culls the population (pulls funding), leaving certain lines of evidence (diet-heart hypothesis) behind to keep reproducing. This is a mechanism by which a false consensus can emerge, forming the basis for a narrative used to formulate “scientific” public policy.

The emergent narrative will be aligned with external reality only insofar as funding agencies select (re-fund) those researchers producing the results most closely aligned with the physical world. But in the world of ideas, peaks in the fitness landscape do not need to correspond to the fittedness of ideas to external reality—they correspond to fittedness to social reality, the set of social relations that determine where people fall in social status hierarchies.

To the extent that funding agencies select researchers for reasons other than empirical accuracy, such as conformity to an existing policy narrative, the "consensus” reflected in the published literature will deviate from empirical reality. Narrative selection governs how the process of science evolves into The Science™ of society.

Two types of evidence contrary to the diet-heart thesis: published & personal

So far, we have primarily looked at weaknesses in the evidence beyond the diet-heart hypothesis, together with the social mechanisms that enabled it to become enshrined in policy and public consciousness despite its shortcomings. Evidence contradicting the diet-heart thesis that emerged at the time was suppressed, and so never counted against it. Over time, however, evidence has stacked up against the diet-heart thesis. That evidence has been summarized elsewhere, from which I will provide snapshot:

Large, randomized controlled trials were conducted in the 1960s and 70s, replacing saturated fats with PUFAs from seed oils in ~67,000 people (reviewed here). Despite the fact that reduced saturated fat intake did lower cholesterol levels, most of these studies did not observe reductions in cardiovascular or total mortality, opposite to what diet-heart predicted. Again, Keys’ thesis had become dominant by the time these results emerged, and they simply weren’t enough to combat the inertia of Keys’ success in driving policy.

The largest epidemiological cohort study ever conducted (PURE), found that saturated fat intake was not associated with cardiovascular disease mortality. In fact, it found that saturated fat intake was associated with lower total mortality and lower risk of stroke.

More than 20 papers reviewing data relevant to the diet-heart hypothesis were published. The vast majority concluded, like this 2020 review, that “the totality of available evidence does not support further limiting the intake of such foods [saturated fat-rich foods].” I spoke to Dr. Ronald Krauss, senior author of that review, all about this on M&M #131.

Let me be clear: no one is saying that arbitrarily high cholesterol is a good thing. The question is, how high is too high? We know that both very high and very low cholesterol levels are clearly linked to negative health outcomes, including increased all-cause mortality risk. We also know that the medical guidelines which set the threshold for “too high” have been moved lower and lower over time, gradually creating a wider and wider window of cholesterol levels within which doctors reflexively prescribe statins (the most profitable pharmaceuticals ever).

In terms of mortality risk, there is a clear “U-shaped” relationship with cholesterol levels. You have elevated risk of death when cholesterol is too high or too low. But statins are often prescribed to people whose cholesterol levels are in the range with the lowest odds of all-cause mortality. I’ve witnessed this directly, with family members. Family doctors simply recommended statins because cholesterol levels were above the magic threshold set by official guidelines—in my experience, physicians are often woefully ignorant as to what the data actually shows regarding cholesterol’s non-linear relationship to mortality, including elevated risk of death when cholesterol levels are too low:

To date, extensive research has failed to support a role for dietary cholesterol intake in the development of cardiovascular disease. Despite the illusion of consensus constructed to demonize saturated fat intake as the main driver of heart disease, no genuine consensus actually exists on this point. There are plenty of eminent researchers who disagree that public health guidelines should recommend limiting saturated fat intake, and comprehensive reviews have conluded, “The totality of available evidence does not support further limiting the intake of such foods.”

Consensus ideas do not automatically evolve from the selection of those that best fit external reality. Consensus ideas evolve from the selection of those that best fit into social narratives that facilitate the status-seeking goals of people, especially high-status people within prestigious organizations. There is no strict requirement that those social goals must align with the ability of the underlying ideas to predict physical outcomes.

The ultimate study is not published—it’s you

At the end of the day, you are your own best source of health data, which is why I get regular bloodwork done. Whether or not any hypothesis is statistically true at the population level, you may or may not conform to the pattern individually. Based on my personal bloodwork data, the predictions of the diet-heart hypothesis have not been born out. For example, here are my total cholesterol levels at three time points:

Between the second third time point, six months elapsed. In that period, staples of my diet were: four pasture-raised eggs on almost every morning; grass-fed cuts of beef several nights per week; wild-caught salmon with liberal amounts of organic avocado mayonnaise 2-3 nights per week; a solid amount of cholesterol-rich seafoods, like shrimp. At home I cook with either butter or coconut oil, and actively minimize my consumption of cholesterol-lowering omega-6 PUFAs (abundant in seed oils). This is a diet high in saturated fat and cholesterol, both of which became more prominent components of my diet after the second time point. Nonetheless, my total and LDL-cholesterol levels became somewhat lower, opposite to what the diet-heart thesis predicts. (My triglycerides, APOB, and inflammatory markers also failed to rise).

Our individual biology, including how we react to foods, may or may not conform to general patterns seen in published literature. Your life is ultimately a stand-alone “n=1” experiment. You can take your health into your own hands: get regular bloodwork done, especially before and after making significant lifestyle changes. It is now possible to affordably do this from the comfort of your home.

Narrative Selection: Transforming the process of science into The Science™ of public policy

Narrative selection describes a social process by which institutions select ideas, such as those published in the scientific literature, for integration into narratives justifying specific social goals. I have elsewhere used this concept to explain the Shirky Principle (“Institutions will try to preserve the problem to which they are the solution”), using the American Diabetes Association as an example. The ADA makes wacky dietary recommendations, including carbohydrate-rich food recipes with added sugars, that seem at odds with empirical evidence and its stated goal of ending diabetes. This is puzzling only if you take their stated goals at face value. It makes sense when you realize that institutions evolve to push narratives promoting an expansion of their influence (and client base).

Here, we have seen how the American Heart Association and policymaking institutions in the US came to promote an illegitimate consensus on the dietary causes of heart disease. That illusion of consensus persists to this day, driving both dietary guidelines and treatment of patients by physicians. This behavior is difficult to explain if we persist in the delusional belief of an unbiased “marketplace of ideas,” but makes perfect sense if we re-imagine the process of “scientific” consensus-making in our society in terms of competition for social status.

In genetic evolution, genes are driven to fixation (high, stable frequency) in a population by natural selection, when they offer a strong survival and reproductive advantage to those carrying them. In memetic evolution, ideas are driven to fixation (widespread adoption) when they become enshrined in public policy and education curriculum. This is not driven by fitness with respect to the physical environment, as with natural selection operating on organisms—it is driven by fitness with respect to the social environment, operating on narratives that influence the structure of social status hierarchies.

High-status individuals (elites) have a natural tendency to fit ideas together into narratives that justify the status quo, offering them security in their high status positions. Lower status individuals who aspire to higher status but are unable achieve it (counter-elites) will attempt to propagate ideas that support counter-narratives. These counter-narratives aim to destabilize the existing social status hierarchy in an attempt to create a new one, with them at the top. Competition among different social factions results in the emergence of competing narratives, culminating in the major political narratives of the general discourse.

This process is evocative of what the Italian political scientist and sociologist Gaetano Mosca called a “political formula”: a set of beliefs, ideologies, or myths that justify the power and authority of the ruling class. As technology has advanced, science has become more and more central to how society functions and the way it is governed. Over time, more and more branches of academic science have become increasingly entangled with the government policymaking apparatus. This can bias entire fields of study, as specific research programs can be selectively re-funded or de-funded based on whether they produce results favorable to the institutions which deploy research capital. The Science™ used to guide public policy may therefore deviate substantially from what is empirically justified.

I have attempted here to sketch a framework, inspired by biological evolution, for how scientific narratives can spread and gain wide acceptance as “settled science” despite a lack of empirical grounding. This happens because ideas are not selected into narratives for widespread dissemination based simply on their ability to predict outcomes in the external world—they are selected for social reasons, by human minds competing for social status. All too human, we never truly escape high school.

The spread of the diet-heart hypothesis by institutions like the AHA is just one example illustrating the phenomenon of narrative selection.

Can you think of others?

For further reading:

Why Are We Getting Fatter? | Part III: Eating Fat Like Never Before

To learn more about the topics covered in this essay, try these episodes of the Mind & Matter podcast:

M&M #131: Dietary Fat, Cholesterol, Cardiovascular Health & Disease, Carbohydrates, Dietary Guidlines, Food Industry & Diet Research | Ronald Krauss, MD

M&M #134: Omega-6-9 Fats, Vegetable & Seed Oils, Sucrose, Processed Food, Metabolic Health & Dietary Origins of Chronic Inflammatory Disease | Artemis Simopoulos, MD

M&M #135: History of Diet Trends & Medical Advice in the US, Fat & Cholesterol, Seed Oils, Processed Food, Ketogenic Diet, Can We Trust Public Health Institutions? | Orrin Devinsky, MD

M&M #140: Obesogens, Oxidative Stress, Dietary Sugars & Fats, Statins, Diabetes & the True Causes of Metabolic Dysfunction & Chronic Disease | Robert Lustig, MD

It's a lovely article. The problem is that public perception no longer has anything to do with reality, and it hasn't for many, many years. Older people were raised on the whole diet-heart hypothesis myth and it's firmly embedded as all the "lifestyle" dietary information they ever need to know, been there done that learned it in 1970, let's move on.

Some of the institutions that gave them this "knowledge" are still doubling down on it. Do you know the most widely read magazine in the US? The AARP newsletter (because it's sent free to more or less every person over 50 whether they want it or not.) Every month I scan AARP and every month I come across at least one squib promoting low fat diets as the responsible choice. Literally 10% of the US population (plus the fallout victims in their households) is mailed this reinforcing bs once a month. The American Diabetes Association is still blathering on about "healthy" (not saturated) fats, and trying to insert wheat and some form of sugar into just about every meal suggestion. Given the choice between steak and PopTarts, I think they'd recommend a "healthy portion" of toaster pastries.

Younger people are being indoctrinated with the equally simplistic and incorrect idea that Eating Plants Healthy (and virtuous), Eating Animals Bad. When you're dealing with these enormous commercially-driven tropes and simplifications as a cheat sheet everyone's using, fighting it with scientific papers is like handing Stephen Hawking's notes to a group of fifth graders and saying see? That's how the universe works. " Uh, thanks, yeah, sun, moon, something about gravity, can I line the birdcage with this?"

Sorry, but we need an Idiot Slogan crawling on the bottom of every youtube.

"Cholesterol, it's what brains crave!"

Fascinating article I’ve thought what you eloquently put into words with the data as well. Also we have very similar diets. I believe Crisco killed more people than smoking.

I grew up on margarine and seed, oils.

It’s almost like these elites formulate these ideas to actually harm us when they know the truth or is it just to sell pharmaceuticals and make money a scam.