The Purpose of (Public Health) Institutions

Institutions evolve to perpetuate the problems they are supposed to eliminate. Has the American Diabetes Association evolved to perpetuate diabetes?

“It is difficult to get a man to understand something when his salary depends on his not understanding it.” —Upton Sinclair

The Shirky Principle

“Institutions will try to preserve the problem to which they are the solution.”

Named after writer Clay Shirky, the principle describes the general tendency of organized groups to prolong the problem they’re meant to solve. Once you grasp it, you start to see it everywhere.

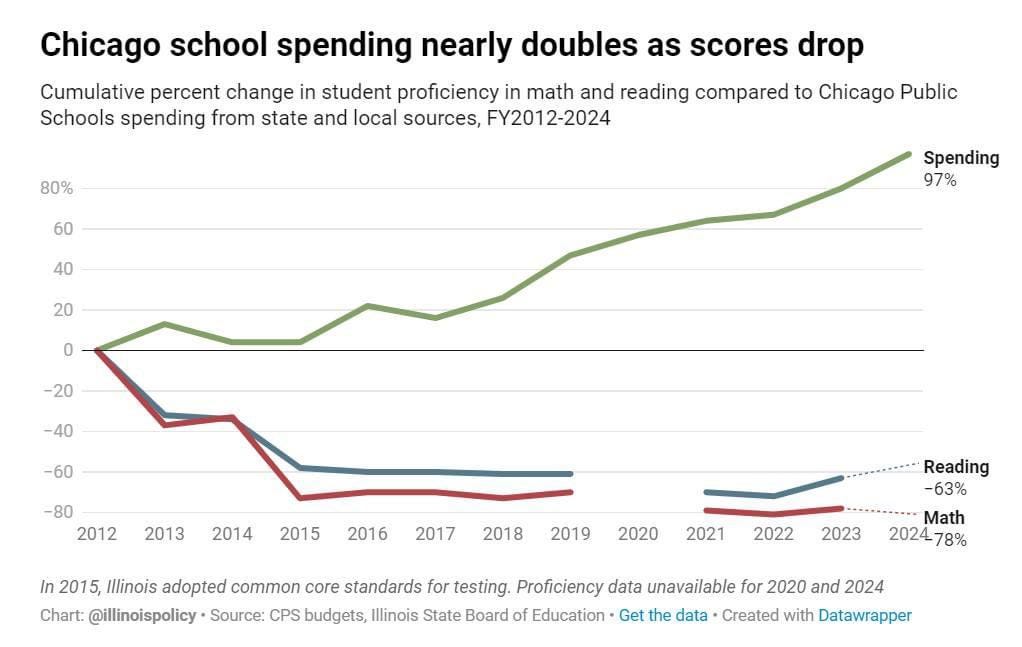

Apparent examples abound. The Department of Homelessness in San Francisco keeps securing a larger and larger annual budget to fight homelessness, which nonetheless continues rising. More and more is spent on public education, but student literacy has declined. Per capita healthcare expenditures go up, the population gets more sickly. Are institutions actually facilitating these problems? Or are they trying harder and harder to combat problems that are independently getting worse? It can be difficult to say for sure, but the pattern is common.

Institutions naturally evolve to maximize their total level of influence because they are composed of humans—people who want secure, high-status positions with comfortable salaries. We want to be influential. We want cool jobs—positions that carry not only healthcare benefits and paid vacation, but bragging rights. Whenever someone tells a stranger, friend, or prospective lover what they do for a living, the preferred response is, “Wow! That’s impressive!”

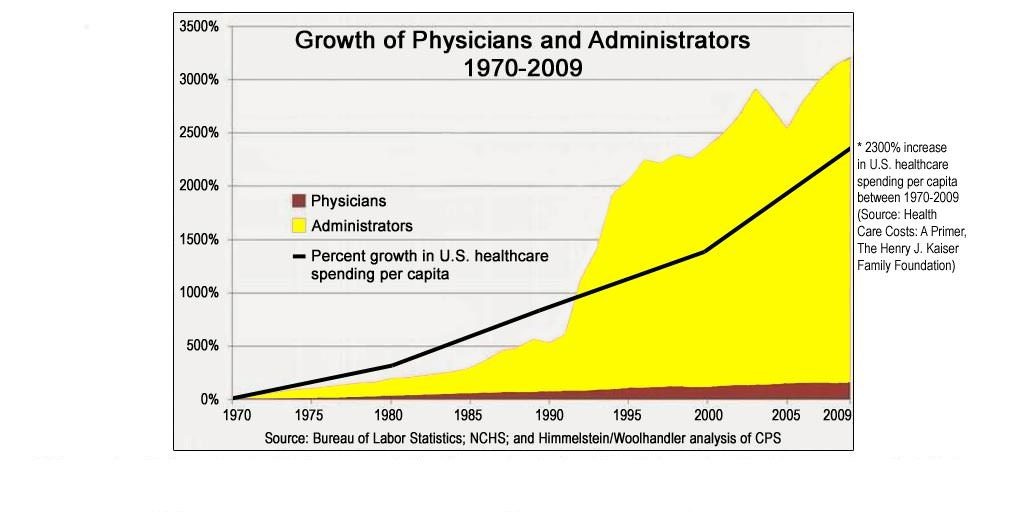

As more capital is acquired by institutions meant to solve a societal problem, a disproportionate amount goes into growing the org itself rather than addressing the problem head-on. If our medical institutions were optimized for maximizing human health, we’d expect them to be good at preventing people from becoming unhealthy in the first place. They would additionally be effective at treating the sick through the efficient deployment of resources. Instead, capital tends to be allocated like this:

Same phenomenon, different institution: universities. Over time, more and more students have paid increasingly obscene fees to attend these institutions. And yet these places of “higher learning” aren’t producing graduates equipped for success outside their hallowed halls. The barista who handed you a latte this morning may have double-majored in something. So what, exactly, are universities doing with all that tuition money? Much goes into hiring non-teaching staff:

The Shirky Principle captures a general tendency of organizational behavior over time, not an absolute law for how all orgs always behave. The tendency to prolong or exacerbate problems emerges as organizations grow, as their ability to acquire funding and grant social status to members increases. They may be founded with genuine intent to eradicate a problem, but literal success nullifies the orgs ability to bestow its members with larger rewards. A never-ending problem provides infinite fuel for growth and justification for more resources.

A commonly cited historical example of the Shirky Principle is the “Cobra effect.” In British colonial India, policymakers wanted to reduce the cobra population. Bounties were offered to anyone who brought in carcasses. An elegant solution—to get rid of cobras, simply pay people to kill them. Locals began hunting cobras and getting paid. Then they realized: more carcasses, more money. People started breeding cobras. Result: more cobras.

It’s not difficult to see why this tendency evolves. In the cobra example, people really did want to get rid of cobras—they’re scary, and they bite. Those who implemented the policy failed to anticipate how people would naturally respond to incentives. Their stated mission was to eradicate cobras, but people were compensated with money in exchange for cobra carcasses. When a company’s mission statement is misaligned with employee incentives, incentives win. This is common, occurring when those who engineer the incentive structure fail to understand how incentives motivate human action. Second-order incentives often emerge that conflict with the desired outcome.

Ignorance is one possible driver of the Shirky Principle. Corruption motivated by status-seeking is another.

Social status, professional incentives & the origins of the Shirky Principle

Humans are social primates. We spontaneously organize ourselves into social status hierarchies. Status is how cool or important you are—your ability to command attention, the currency of social status. It’s more valuable to be higher status because it can be used to influence peoples’ attention to your benefit. Not everyone aspires to be Prom King or CEO, but no one wants to be unimportant or become less cool. Some do whatever it takes to acquire as much status as possible. Others seek security, content with the status they hold. Nobody wants to fall.

When you’re part of an organization, you naturally want to maintain or increase your status within it, especially when your livelihood is at stake. We want promotions, not demotions—bigger budgets, not smaller ones. The larger the problem an organization aims to solve, the more resources it can attract to solve it. What’s cooler? Running a tiny org with a modest budget and two staff members? Or heading a billion-dollar operation with hundreds of people on a mission to save the planet? Who will be more motivated to keep things rolling?

Big budgets and important jobs attract people who want a slice of the pie. People generally aren’t content with one small piece of pie—they want everlasting pie. Basic emotions drive our hunger for status—envy, greed, lust. We adapt to what we get. Hunger transforms into gluttony. Securing more status, we feel pride—when it’s threatened, wrath. With security often comes sloth. People work hard because they strive to get somewhere. That somewhere is a secure, high-status position. Lots of pie, little hassle. Nobody wants to be an intern forever.

The Diabetes Problem: a large, growing pie

Diabetes is a massive, global problem. Ballooning numbers of people are afflicted. Chronic illness is also very expensive, forcing people to spend a lot of money. The pie is very big. Big problems require big solutions. To motivate people, you have to offer them a big enough piece of the pie. According to the American Diabetes Association, their mission is “to prevent and cure diabetes.” An ambitious and noble goal.

The essential problem: if the mission is fulfilled, the pie is gone. Remember the cobra problem? People want pie.

From the Shirky Principle we would expect that, with time, an institution like ADA would adopt behaviors that prolong the problem of diabetes rather than those that hasten it’s resolution. But come on, can this really be the world we’re in? How on Earth could a nonprofit like ADA become structured to prolong the problem of diabetes? Are we to believe it’s run by a cabal of people who want more diabetes in the world?

The key to understanding the Shirky Principle is to recognize that it points to an organic tendency arising from the ways humans respond to incentives. No conspiracy is required, just basic emotions. The Cobra Problem was made worse because policy architects failed to correctly anticipate how human behavior would adapt to incentives.

Has the ADA evolved to prolong the diabetes problem rather than solve it? To prime our intuitions before analyzing this question in more detail, consider the size of the problem and how the ADA is positioned within society to engage it. In their own words:

“The ADA raised $122.3 million, including initial funding for Health Equity Now, our multi-year initiative that envisions a future without unjust health disparities. Our expenses totaled $108.6 million, 70% of which went directly toward our mission: to prevent and cure diabetes and to improve the lives of all people affected by diabetes.” —ADA, 2020 annual report

Among other things, that budget goes to pay the salaries of staff (which presumably counts as “directly toward our mission”). For executives, that means very comfortable six-figure salaries. According to Glassdoor, VPs and Senior Executives make anywhere from $124,000 to $297,000 annually (plus benefits). Directors often earn six-figures as well. According to LinkedIn, there are quite of few people carrying these titles. Not bad for a non-profit. Again, big problems require big solutions. Pie motivates.

A thought experiment: through some miraculous breakthrough, diabetes disappears tomorrow. What happens to ADA? Does it dissolve itself? There’s no need to renew their annual budget or keep taking donations—diabetes is over. Do they sell off their assets to fund generous severance packages for executives and other staff, as a thank you for realizing their stated mission?

Many people seem to believe that ADA is indeed prolonging the problem of diabetes. They argue it promotes diets that make the condition persist, that it’s staffed by former employees of junk food makers, and takes money from private corporations that profit from chronic illness. These are reasons why, according to some, ADA makes poor diet recommendations to people.

Let’s start by unpacking a recent controversy that erupted in response to one of ADA’s meal planning strategies for diabetes.

The Plate Method: ADA’s simple meal planning approach

The American Diabetes Association (ADA) recently got lots of attention when it advertised the “Diabetes Plate Method.” Their widely shared video post amassed millions of views in short order:

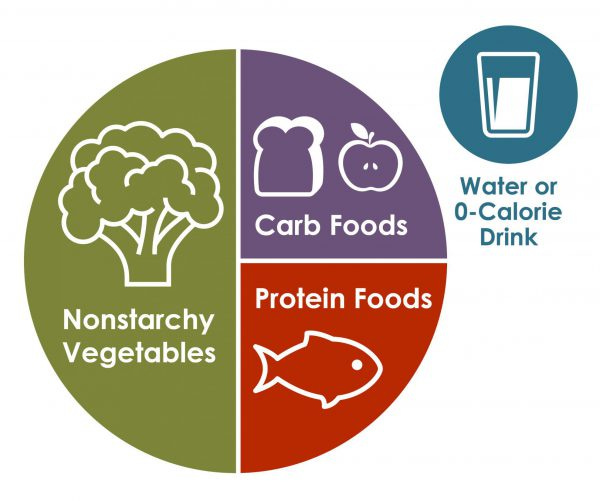

From ADA’s website, the “Plate Method” works like this:

“The Diabetes Plate Method is the easiest way to create healthy meals that can help manage blood sugar. Using this method, you can create perfectly portioned meals with a healthy balance of vegetables, protein, and carbohydrates—without any counting, calculating, weighing, or measuring. All you need is a plate!”

The method is simple, as it should be. The goal is to influence the behavior of the masses, which requires a simple, easy-to-understand approach. Normal, everyday people are busy—jobs, children, and little time or inclination to get lost in the weeds of “nutrition science.” For this I commend the ADA. We need easy-to-follow methods ordinary people can put into action. No easy task. Anyone putting forward such plan will take heat, and people with public opinions on diet are often animated by a kind of religious zeal.

The Plate Method:

Half for non-starchy veggies. Vegetables with low carbohydrate content like asparagus, broccoli, or carrots.

One-quarter for lean (low-fat) protein foods, ranging from animal meat (beef, poultry, seafood) to cheese and plant-based protein sources (beans, lentils, nuts, tofu, etc.)

One-quarter for carbohydrate foods—“good carbs” like whole grains (brown rice, oatmeal, quinoa, etc.), starchy veggies (potatoes or green peas), beans and legumes. A small portion of fruit or low-fat dairy on the side.

Water or a zero-calorie drink. No sugar-filled sodas.

The ADA thinks this is good advice for managing diabetes. Others disagree.

So is the ADA providing good advice or bad? To approach this, we need to understand the basics of insulin resistance and how it relates to dietary macronutrients. Our main focus will be on which macros are the biggest drivers of insulin resistance. In particular, we need to understand how “good” and “bad” carbs differ with respect to insulin.

Food, Carbs & Insulin Resistance

Insulin resistance is a key component of type II diabetes, obesity, and other bad things. You don’t want to be insulin resistant. Cells decrease their responsiveness to insulin when there’s too much of it for too long. It is a reversible cellular adaptation to chronic, excess insulin (although irreversible changes may occur with prolonged insulin resistance). The natural way to reverse insulin resistance is to lower insulin, which can be done by eating less, especially of foods that trigger lots of insulin release.

Diabetics suffer from poor glucose regulation, which is why their blood sugar levels can get dangerously high (hyperglycemia). To reverse large glucose spikes, triggered by poor dietary choices, they can inject themselves with insulin. This solves their short-term problem (high blood sugar) but exacerbates the underlying insulin resistance. It’s sort of like an opioid addict taking a large hit of heroin to relieve withdrawal symptoms. The immediate symptoms dissipate, but the underlying issue is made worse. Tradeoffs.

Carbohydrates, especially simple sugars, generally raise insulin levels more than fats or proteins. I’ve previously dissected just how different so-called “good” carbs are compared to “bad” ones. Most people would agree that some level of carb restriction is needed to combat insulin resistance. There is disagreement on how much is enough and what “good” carbohydrates actually are.

Before proceeding with our analysis of ADA, let’s get a basic handle on what the literature says about the effectiveness of low carb vs. other diets in terms of insulin levels and diabetes management.

Low-carb diets and type II diabetes: how well do they work?

ADA often recommends low-to-moderate carbohydrate diets to patients, emphasizing what it considers to be “good” carbs. They do not recommend very low or no-carb diets (e.g. ketogenic), stating these can be difficult for patients to implement and maintain. They do emphasize low fat diets and “good” carbs in moderation. (For an analysis of why certain fats have been demonized as “bad” over the years, see my conversation with physician-scientist Dr. Orrin Devinsky)

We’ll start with a study of n=83 overweight adults (BMI>28), randomly assigned to three different isocaloric diets for several weeks (i.e. equivalent calories in each meal). The three diets:

Notice the basic differences. The very low-carb diet has full fat cheese, whole milk, meat, eggs, nuts, and salad. The other two diets have bread wholemeal as the primary carb source, together with things like fruit bars, skim milk, reduced fat dairy alternatives, and some kind of meat. These very low fat and high unsaturated fat diets above are roughly in line with ADA advice—low levels of “bad” fats together with “good” carb sources like whole grains, fruit, and beans.

Here’s how insulin responses looked at the beginning and end of the experiment for each meal group:

All groups experienced a modest decrease in insulin by the end. But for the duration of the study, the very low-carb meal group had much lower insulin levels, roughly one-third of what was seen with the other diets. The very low-carb diet was indeed very low—just 3% of calories from carbs. That’s one study.

Another study measured 24-hour blood glucose and insulin levels in adults with type II diabetes, half on a low-carb diet (~21 grams of carbs/day) and half on their usual high-carb diet:

Studies like this show that on low-carb diets, insulin levels not only rise less after meals but stay lower throughout the day, compared to high-carb diets.

These are just two individual studies in a vast sea of literature. It’s confusing to navigate, easy to cherry-pick results. To get a more general sense of how low-carb diets compare to others with respect to insulin resistance, let’s consider studies from the past ten years, limited to those with insulin measurements from trials where isocaloric diets were given for at least several weeks.

A 2021 meta-analysis compiled randomized clinical trials evaluating low and very low-carb diets compared to various control diets for at least 12 weeks in adults with type II diabetes. Compared to control diets, low-carb diets achieved higher rates of diabetes remission (57% vs. 31%). Very low-carb diets were less likely to be adhered to than low-carb diets, but were effective in those who stuck to them. The main result is worth repeating: many weeks on a low-carb diet led to remission of diabetes in many patients.

In this 2019 trial, n=28 adults with type II diabetes were randomized assigned to receive either a “conventional diabetes” diet (50/17/33 balance of carbs/protein/fat) or a “carb-reduced high-protein diet” (30/30/40 balance of carbs/protein/fat). The carb-restricted group saw lower levels of post-meal insulin (as well as other markers).

In this 2022 study, n=60 overweight or obese patients with newly diagnosed type II diabetes were given one of two diets for 12 weeks: A ketogenic diet vs. a variable control diet with limits on max carbs, protein, and fat such that carbs were the most abundant calorie source. Both groups saw significant, beneficial changes in most measured parameters, but the keto group generally saw larger shifts. This included fasting insulin at half the level seen in the control group.

A 2015 study looked at n=69 overweight/obese adults at risk for diabetes. They received either a low-fat or low-carb diet for eight weeks. In general, the low-carb diet had beneficial effects on measured outcomes, including a lesser insulin response following meals compared to the low-fat group.

The point here is not to argue that low-carb diets are the only viable strategy for lowering insulin and improving diabetes, or even that they’re superior to other approaches. The point is simply that, when people adhere to low or very low-carb whole food diets for several weeks, they generally see improvements in key health parameters relevant to diabetes, including lower insulin. These diets often perform better than alternative, higher-carb or low-fat diets, and can even lead to remission of type II diabetes.

None of this should be too surprising given what we know about the underlying biology. Carbohydrates generally drive a larger insulin response than fats and proteins, so it makes sense that carb restriction would help improve insulin sensitivity and help manage diabetes.

Nutrition is complicated. Biology, complex. But improving insulin sensitivity and reversing diabetes through diet probably has to involve some level of carb restriction for most people. The question is: how much? Is it more effective to be aggressive and promote very low-carb diets (e.g. the ketogenic diet), or is it enough to get people to swap out “bad” carbs for “good” ones?

One of the major problems with ultra-low carb diets like keto is that they’re difficult for the average person to stick to. If something works but people can’t stick with it, that’s not very helpful. On the other hand, we know that the divide between “good” and “bad carbs can be murky. Many so-called “good” carbs result in insulin responses comparable to, or even greater than, those of “bad” carbs.

Let’s look at the dietary recommendations and arguments of the ADA in more detail. We want to represent their perspective fairly, keeping in mind that we’re talking about dietary strategies meant to influence the eating habits of everyday people. Any viable strategy has to not only be effective if put into practice, but feasible for the average patient to implement.

Characterizing ADA’s dietary advice

Let’s point out what the ADA’s “Plate Method” does right. These things should not be controversial:

Simplicity. Anyone can comprehend this approach. Heroic efforts are not required for implementation.

Whole foods. With some exceptions, ADA is not recommending processed foods (at least not in this document).

Portion control. They’re laying out a simple visual for portion management, supplemented with basic measurements for how to portion out different foods.

Specific whole food recommendations are given for each class of foods in their document. Many would argue with various particulars, ranging from emphasis on low-fat meat and dairy to their characterization of seed oils as “healthy fats.” All valid points. For our purposes here, we’ll focus on their carbohydrate recommendations.

From the image above, you can see that ADA recommends several types of foods as carb-sources—whole grains and things like beans and lentils, as these contain protein or fiber. Consuming more protein or fiber together with a given carb-rich food will generally be beneficial in terms of blood glucose and insulin. But as I’ve explored elsewhere, many “good” carbs containing fiber or protein produce insulin responses comparable to, and sometimes even greater than, “bad” carbs like white bread. This can be true for everything from wholegrain breads to potatoes and beans. Recommending carbs be consumed with fiber or protein is directionally good advice, but is not a surefire method for managing blood glucose and insulin levels.

Stepping back, what about total carbohydrate consumption? With the Plate Method, 50% of the plate is for non-starchy vegetables, which are low in calories. One-quarter is for carb foods. In this post, one ADA employee cited data indicating that the average American consumes about 50% of calories from carbs, and that their meal plan would result in consumption of about half that level. Let’s just call it 25%—one-quarter of daily calories from carbs.

Based on the clinical literature, “low-carb” is often applied to diets with 25% or fewer calories coming from carbs. “Very low-carb” diets are typically 10% or less. There’s no universal definition for these things but it’s fair to call the ADA’s method a low-to-moderate carb approach. It certainly isn’t very low-carb.

ADA seems to be recommending moderate carb restriction. They aren’t telling people to drink Coca-Cola and eat Sour Patch Kids, which would be insane and a dead giveaway that they’re completely off the reservation. Clearly that’s not what’s going on.

Recall the Shirky Principle. It does not state that institutions will blatantly try to make the problem worse, but that they will tend to evolve practices that preserve the problem. This can be accomplished by adopting strategies that don’t help very much, enabling the problem to persist for as long as possible. This is actually a good long-term strategy. Taking actions with little impact on the problem, rather than those that blatantly make it worse, helps to minimize any pushback that would undermine the org’s ability to expand. At the same time, an incremental, conservative approach provides a kind of protective veneer—it looks like you’re trying to do something. You’re being realistic, following established guidelines, and not promoting anything where the science isn’t settled. Talking points like this are important elements in the narratives constructed to justify an organization’s strategy (we’ll dissect the process of narrative selection in more detail below).

Think about it.

If ADA hired the Chief Marketing Officer of Sour Patch Kids as CEO and they began recommending three square meals of sugary candy per day, there’d be some kind of major reaction to such obvious absurdity. But what if it seems, to most people, like ADA is making reasonable, moderate recommendations in-line with USDA dietary guidelines? What if ADA staff really believe they’re doing good and promoting wellness? What if you hire from respectable organizations like the American Heart Association and recruit people with years of experience as dietitians? Aren’t all of those things what you would naturally expect, and hope, a major institution does?

ADA is recommending moderate carb restriction, portion control, and whole foods. Hardly damnable. Why are some people so worked up about their Plate Method? Let’s take a look at what critics have said and examine some of ADA’a specific meal recommendations more closely, including who sponsors them.

ADA’s Diet Plan: what’s the fuss about?

When ADA posted it’s Plate Method video on social media, many pounced. One example:

In essence, those critical of ADA’s diet recommendations argue that it’s promoting too much carb consumption. Given that carbohydrates spike insulin levels more than fat and proteins, this makes sense. Those with diabetes and prediabetes (now the majority of adults) need to lower their insulin levels, which means changing their diet. Since carbs spike insulin more than other macronutrients, it makes sense to focus on cutting down on carbs as much as possible.

The response to this reasoning, from the ADA’s Director of Nutrition:

“In my over 30 years of experience as a Public Health Nutritionist and Registered Dietitian, I’ve found that going from a high or moderate carbohydrate meal pattern to a much lower carbohydrate pattern for someone who has not paid much attention to their nutrition is extremely challenging. This often requires a stepwise and incremental approach, with the assistance of their health care team, as they learn all these new skills. As success is achieved, newer strategies can be added to continue moving along the continuum for further success.” -Stacey Krawczyk, LinkedIn (emphasis added)

My summary of the argument: many people have seen success, including diabetes remission, with very low-carb diets. The effectiveness of very low-carb diets at reducing insulin is well-documented and there are many anecdotal success stories out there. The counter-argument from ADA is that, although very low-carb diets may often be effective, they are not practical to implement and sustain for people who’ve eaten high-carb diets for many years—an incremental, stepwise approach to diet should therefore be taken to gradually nudge their eating habits in a new direction.

These points all seem pretty reasonable to me. After all, the average American has been eating a high-carb, processed food-rich diet for life. Many are true addicts who likely can’t regulate their own behavior enough to sustain a very low-carb diet. ADA needs to balance what’s most effective at treating diabetes with what people can actually manage in their lives.

Within the Shirky Principle framework, I’d expect an institution like ADA to evolve—it’s behavior should change over time, as it learns through trial-and-error which of its actions leads to growth. If it has morphed into an organization enabling the problem of diabetes to persist, then its dietary recommendations will have shifted away from approaches that help reverse diabetes, toward those that enable its persistence. I can imagine two potential drivers:

Accumulation of corporate sponsors who benefit from diabetes—providing revenue streams to fuel growth;

Infiltration of the org itself by former employees of such corporations.

ADA’s sponsored meal & snack plans.

There’s a difference between thoughtful, incremental dietary recommendations and enablement. When you start to look at ADA’s specific food recommendations, it quickly becomes clear why people call them out. A common point of criticism: ADA promotes snacks and meals containing added sugar. Here’s one from the ADA website, which it calls the “Power Snack Mix”:

It’s questionable as to why ADA is promoting snacking at all, but this one is downright strange. Based on the ingredients, the primary macronutrient is carbohydrates. One of the four ingredients is chocolate chips, more or less just straight sugar. I’m doing my best to be fair-minded here, but this is just plain weird for an org whose mission is supposed to be eradicating diabetes. Snack on chocolate chips? What?

Things get more strange with further inspection of their meal recommendations. For example, here’s a carb-heavy pasta dish. Even if we accept the argument that pastas can be “good carbs” which don’t spike insulin levels as much as simple sugars, one of the ingredients here is… added sugar!

Adding pure sugar to any dish is a bad idea for those interested in managing insulin levels, especially someone who is already insulin resistant. What could possibly possess an organization to recommend added sugar as an ingredient to an already carb-heavy meal? As many have pointed out, the answer appears to be: advertisers.

Carb-rich pasta with added sugar, brought to you by DaVita Kidney Care, proud partner of ADA!

DaVita is a private company. They run kidney dialysis centers. Many diabetics end up in these places due to kidney damage caused by chronically high blood sugar. The name “DaVita” is an adaptation of an Italian phrase meaning, “Giving life.” That’s their stated mission—“we are dedicated to an unwavering pursuit of a healthier tomorrow.”

Recall the Cobra Problem. If you want to understand real-world outcomes driven by human behavior, ignore mission statements. Think through incentives. The more people on dialysis, the more revenue DaVita generates. Some of that revenue is clearly going to ADA in the form of meal sponsorships promoting carb-rich meals with added sugar. Those are simple, empirical facts. Where do incentives point? How will humans behave?

There are many such meal examples on ADA’s website, some of which are sponsored private companies whose revenue goes up the more people there are living with chronic metabolic illnesses like diabetes. You can find carb-heavy meals of all kinds, ranging from “fruit-filled pancake puffs” to “whole grain chicken & waffles” and fruit punches that contain added sugar on top of orange juice.

Again, there’s no need to assume anyone, in any of these organizations, is a cynical actor. No conspiracy required. Just consider the basic incentives placed on flesh-and-blood, status-seeking humans. DaVita Kidney Care wants its revenue streams to grow, not shrink. ADA wants bigger sponsorships and more donations to fund its important mission. Everyone wants promotions, demotions. There are sales targets to hit. Bragging rights are at stake.

A fun question to ponder: does the ADA award employees annual bonuses? If so, what kinds of metrics are these payouts based on?

ADA not only promotes carb-rich meals and snacks with added sugars, they receive multimillion dollar donations (presumably tax-deductible) from the some of the world’s top insulin makers, such as Eli Lilly, Novo Nordisk, and Sanofi. These pharmaceutical giants produce the insulin that many diabetics inject. When do they shoot up? When their blood sugar spikes dangerously high. This happens when they make unhealthy dietary choices, like eating chocolate chips. More people with diabetes eating chocolate chips means more insulin sales.

Above, we listed two possible mechanisms that could drive ADA to adopt behaviors enabling the problem of diabetes to grow: (1) accumulation of corporate sponsors who benefit from a larger pool of diabetes patients (customers); (2) infiltration of the org itself by former employees of such corporations. The first of these is clearly in play. What about the second?

To the extent that ADA receives funding from and is operated by people tied to entities with a financial interest in the persistence of diabetes, we would expect its behavior to move in the direction of serving those interests. If ADA has itself accumulated staff from such entities, it’s behavior can be influenced internally. To the extent that internal (staff) and external (sponsors) influences are aligned, they should nudge the organization’s behavior in the same general direction. Over time, this would shift its dietary recommendations towards those that preserve the problem of diabetes.

Everybody wants more pie.

Evolution of ADA

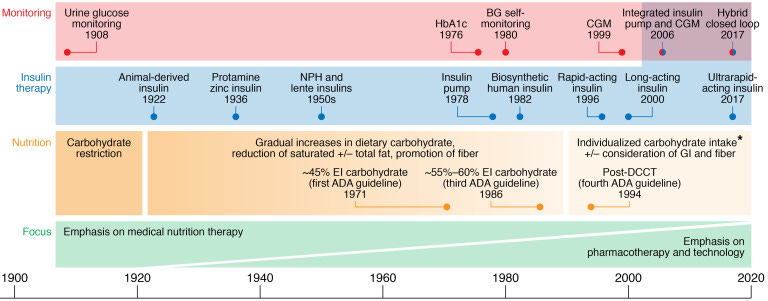

Carb-restriction as a treatment for diabetes has a fascinating history. As far back as the late 1700s, it was observed that carb-rich foods like bread and sugar aggravated diabetes symptoms and low-carb diets were recommended to diabetics. After the discovery of insulin in the early 1920s, dietary interventions began to fall out of favor. Pharmacotherapy (insulin injections) became more and more common.

To give a sense for how mainstream physicians approached diabetes prior to the discovery of insulin, check out the “starch-free diet.” It was devised by Dr. Herman Mosenthal, published in his 1921 book, Diabetes mellitus; a system of diets:

The present system of diets has been designed with the object of allowing any patient or nurse, without special training in dietetics, to carry out the proper rationing for cases of diabetes mellitus. These diet lists have been in successful use in a number of hospitals and clinics for several years. -Dr. Herman Mosenthal (1921)

That was printed right around the discovery of insulin. Mosenthal would go on to be a founding member of ADA (established in 1939). He served as President in the 1940s and passed away in 1954. It wasn’t until 1971 that ADA released its first official dietary recommendations, which deviated significantly from Dr. Mosenthal’s starch-free diet.

ADA released dietary guidelines again in 1986. Assuming ADA would have endorsed something like its founding memberl’s starch-free diet when it was established, here’s how ADA’s dietary recommendations evolved from 1939-1986:

1939—Mosenthal’s “starch-free diet,” a very low-carb diet urging diabetics to avoid carb sources like sugars, grains, and fruit.

1971—Approximately 45% of calories from carbs was considered acceptable, apparently based on nothing more than population norms at the time.

1986—Approximately 55-60% of calories from carbs and total fat restricted to <30% of calories.

There was a transition from lower to higher carbohydrate intake, and from higher to lower fat intake. By the mid-1980s, American dietary guidelines had moved squarely in the direction of carbs good, fats bad. This was driven largely be the belief that blood cholesterol levels are the primary driver of cardiovascular disease, resulting in the demonization of “bad” fats (saturated) and promotion of “good carbs” like whole grains. Mainstream medical institutions like the American Heart Association disseminated the official creed in creative ways, such as the infamous “food pyramid.” In large part, Americans listened.

As physician-scientist Dr. Orrin Devinsky explained to me, the evidence supporting this narrative was never strong. Here are a couple key changes in Americans’ diet patterns, based on analysis in this study, which I discussed in detail with Dr. Devinsky.

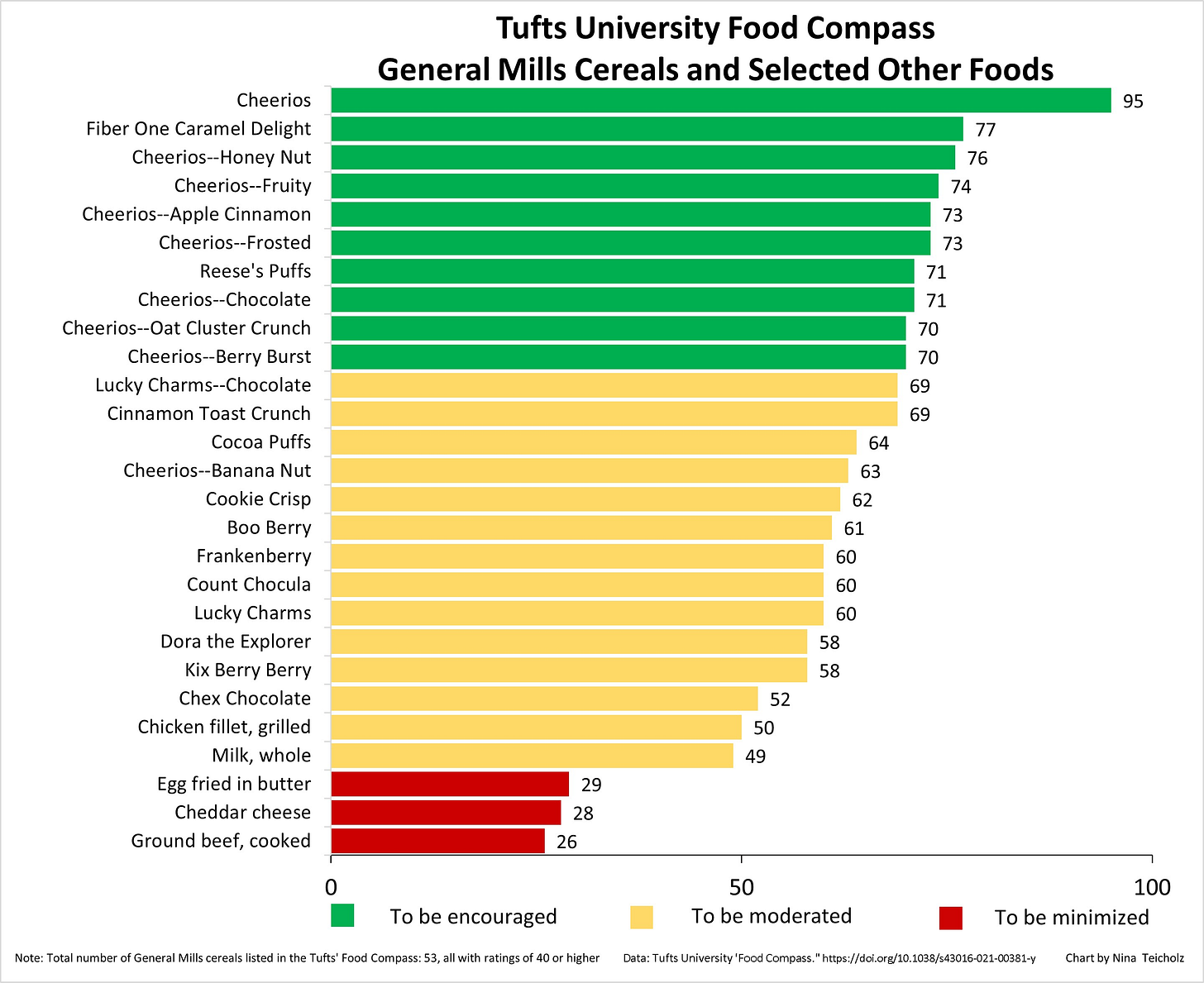

Since the mid-1900s, people transitioned away from “bad” animal fats (saturated), replacing them with “good” fats (polyunsaturated), such as “heart healthy” seed oils. To this day that’s the message we get from institutions like the American Heart Association, which certifies processed foods like Cheerios as “heart healthy.”

From the 1960s to the 1980s, per capita processed grain availability increased 113%. From the 1980s to the 1990s, it increased 47%.

These shifts in food production went more or less in the opposite direction from what Dr. Mosenthal was recommending at the time of ADA’s founding. After his death and the dissemination of official USDA dietary guidelines, amplified by mainstream health institutions, how did diabetes rates change?

Diabetes rates have moved in one direction since the discovery of insulin, the founding and growth of ADA, and successive waves of dietary recommendations set forth by our mainstream institutions. There are multiple, competing narratives that can explain this general pattern.

One interpretation is that Americans aren’t following the guidelines. Institutions are providing good, evidence-based advice. American people just aren’t taking it. There may be some truth to this, but it doesn’t make total sense. As indicated above and explored in more detail here, Americans have shifted their diets in the direction of the guidelines. They started eating a lot of carbs in the form of grains—you know, the base of the food pyramid advice I was inculcated with as a child. A common response: well, we’re more sedentary. Not true either—obesity and diabetes rates have climbed despite evidence we are less sedentary than we once were.

Another interpretation: diabetes rates have continued climbing decade after decade because of the dietary guidelines set forth by mainstream institutions. We have forgotten what physicians like Dr. Mosenthal and others knew over 100 years ago: carbohydrates, especially sugar and refined grains, exacerbate diabetes. We also know why: they drive insulin. The discovery and use of insulin as an injectable medicine gave us an easy way to acutely treat one of the major symptoms of diabetes (high blood sugar), enabling us to relax our focus on lifestyle interventions that can treat and even reverse the underlying biological problem (insulin resistance).

The simultaneous use of drugs (e.g. insulin) that treat the symptoms but not causes of metabolic dysfunction, together with diets that do not reverse the underlying metabolic problem (insulin resistance), creates a valuable commodity: people with high lifetime customer value. The longer someone lives with diabetes, the longer they’re around to continue spending money on medicines and foods, and the more justification there is for an expansion of ADA’s influence (and budgets).

Of course, there are other interpretations of what’s going on.

Following the Science: natural selection, narrative selection

A natural counterargument here, as to why ADA’s dietary recommendations have changed over time, is that they’re simply following the science. We’ve learned a lot about diabetes, metabolism, and nutrition since Dr. Mosenthal’s 1921 starch diet. Many scientific papers were published in the past century. Many have been supported by ADA, which has devoted $950 million to “innovation studies” since the start of its Research Programs in 1952. How is that not a good thing? A large non-profit institution has injected hundreds of millions of dollars into research, expanding our knowledge base. Because that knowledge base grows and changes over time, we must continually update what we believe and recommend to patients. That’s scientific progress, isn’t it?

For better or worse, how scientific research is funded plays a big role in how it’s conducted, how the results are published and distributed, and whether labs get re-funded after publishing work fueled by their initial grants. As we’ll see, the shear size of the published literature—filled with a mixture of rigorous science, sloppy science, and conflicts of interest—provides an invaluable substrate from which human organizations can select results to fit desired narratives. Call this process “narrative selection,” by analogy with natural selection.

Contaminated science: how industry funding generates the substrate for narrative selection

For better or worse, the history of research on human diet, nutrition, and metabolism is filled with examples of suspicious funding, conflicts of interest (often unreported), and results based on sloppy and even fraudulent work. There are many, many examples that illustrate the corrupting influence that funding sources have had on research. Here’s just a few high-profile, well-documented cases:

Ancel Keys’ infamous “seven countries study” has influenced generations of scientists and the entire mainstream medical establishment for decades. (It even has it’s own website). That influence is still reflected in the practice of physicians and medical organizations today, despite the now well-known fact that Keys’ data was problematic in various ways. Studies contradicting his ‘diet-heart hypothesis’ were often ridiculed or suppressed (e.g., see Dr. Orrin Devinsky’s commentary on the ‘Framingham Heart Study,’ at ~1:16:51 in M&M #135)

For decades, the sugar industry dolled out large sums of money “that successfully cast doubt about the hazards of sucrose while promoting fat as the dietary culprit in coronary heart disease.” Corruption of the scientific process in the service of narrative formation.

It’s well-known that mainstream medical organizations like the American Heart Association practically owe their existence to large corporate donors. For example, Proctor & Gamble gave millions of dollars to AHA, influencing them to tell consumers to replace butter and “bad fats” with the “heart healthy” seed oils that P&G wanted to sell. This narrative yields dividends to this day.

Notice how mutually beneficial partnerships between for- and non-profits can arise, as in the case of Proctor & Gamble and AHA. P&G needed to create a narrative to motivate people to buy its new product (seed oils). To do this, they facilitated the expansion of another organization (AHA) by injecting money via donations. Like human growth hormone into a bod-builder’s buttocks, AHA’s budget and influence grew. Their growing prestige was used to propagate the narrative that P&G’s “vegetable” oils were good for the heart. A symbiotic relationship between expansion-hungry organizations, the growth of one facilitating growth of the other.

You don’t have to look far to see how widespread the food industry’s influence on research is. Everyone from Kellogg’s to Nestle provides funding—lots and lots of it. The same is true of pharmaceutical companies that profit from the growing pool of chronic disease sufferers. These companies not only fund scientists directly, they sponsor medical organizations—ADA, AHA, etc. In turn, these institutions use that money to fund research, advertise meal plans to consumers, and pay staff. To the extent that the recommendations of these non-profits drive consumer behaviors that are good for their sponsors, a mutually advantageous ecosystem is created—an environment in which the goal of every organization (expansion) in the network is reinforced through reciprocal financial benefit, ultimately powered by consumer behavior motivated by the narratives they subscribe to.

All of these organizations vary in size and structure, but none of them wants their domain of influence (or revenue streams) to shrink. All of them rely on the construction of narratives, stories people must believe to motivate their behavior in ways that fuel the organization. These narratives take diverse forms, ranging from the product marketing stories compelling consumers to buy products to virtue signaling messages of social good non-profits use to drive donations.

Labyrinthine financial ties connect for-profit companies, non-profit institutions, and research labs. These can be invisible, as when scientists and physicians fail to disclose conflicts of interest. To give just one example, the lead author of this paper from the American Academy of Pediatrics failed to disclose nearly $225,000 in funding from Big Pharma. That paper was meant to cast doubt on the effectiveness of low-carb diets in youth with obesity and diabetes. Because it’s published, peer-reviewed research by credentialed experts, it can be cited as evidence against low-carb diets for people with metabolic conditions. One then has justification to promote stories involving “carb moderation” and “good carbs,” providing the impetus for things like ADA’s cheerios and chocolate chip-filled “power snack”, which can be called an “evidence-based” recommendation.

An uncomfortable truth about the scientific literature: you can dig up a set of papers to justify just about any conclusion you want.

Science is difficult and expensive. Labs often produces conflicting results. If you fund lots of different research labs, you’re bound to see a diverse results, some of which have conflicting interpretations. This creates a two-pronged opportunity for anyone looking for a science-backed narrative to justify behavior that serves their organization’s interests: (1) Selectively re-fund the labs who produced the results you like best, biasing the field over time; (2) Selectively point to a subset of results to promote your preferred narrative, or else throw up your hands and say things like, “The science isn’t settled,” “More research is needed,” or “Look at all the research we’re funding!” Merchants of doubt have much use for unsettled science.

A good example of how the official research process can be artificially skewed by special interests is illustrated by this re-evaluation of data from the Minnesota Coronary Experiment (MCE) of 1968-73. This study conflicted the dominant narrative that blood cholesterol levels are a major driven of heart disease, but the data went unpublished until 2016. It showed that even though replacement of “bad” saturated fat with “good” linoleic acid (seed oils) did effectively lower serum cholesterol, this did not translate to lower risk of heart disease or mortality. In other words, a large study contradicting the dominant narrative espoused by mainstream health institutions sat idle, collecting dust, for decades.

“Findings from the Minnesota Coronary Experiment add to growing evidence that incomplete publication has contributed to overestimation of the benefits of replacing saturated fat with vegetable oils rich in linoleic acid.” —Ramsden et al. (2016)

I’m not saying this means that each and every study with industry funding is wrong and needs to be thrown out, but we also can’t be so naive that we “follow the science” by blindly pointing to published research. Even worse: blindly following the story someone else is telling just because they have PubMed citations. When “the science” says there’s only weak evidence supporting the recommendation of low-carb diets to people with impaired glucose metabolism, we should probably take note of when that work is funded by General Mills.

The process of narrative selection

Biological diversity is the substrate of natural selection, the process by which organismal forms are “fitted” to the physical environment through the selective survival and reproduction of those best adapted to the environment. Evidential diversity is the substrate for narrative selection, the process by which specific conclusions are fitted to narratives which motivate human behavior.

Everyone has ideas. For any idea we encounter, there’s a chance we believe in and act on that idea. Experts are a special subset of people possessing specialized knowledge and whose ideas carry extra weight. All other things being equal, the more you’re seen as an expert the more likely your ideas are to replicate in others’ minds upon exposure. Scientific results published through the official peer-review apparatus are shareable units of specialized, expert knowledge. These bits of knowledge can be amplified by institutions and individuals, often in mutated form. The shear quantity of publications generated year after year provides a rich substrate for narrative selection.

There are many funders of research—governments, for-profit corporations, non-profit institutions—fueling mass production of scientific papers. From the diversity of papers generated, human minds curate (select) and interpret (mutate) the findings. The resulting ideas can then be crafted into a narrative—a press release, recorded speech, or Substack article—vehicles by which the ideas are transmitted to others minds (reproduction). The most successful narratives are those most effective at motivating people to further propagate the narrative—either by motivating them to transmit the narrative themselves or to support the expansion of other voices amplifying the narrative (e.g. tax-deductible donations to ADA, subscribing to this Substack, etc.).

In biological evolution, natural selection is imposed by the physical environment, which dictates whether or not a given organismal form reproduces. In ideational evolution, narrative selection is imposed by the human mind, which dictates whether or not a given idea is communicated. Human minds encode and share information in the form of stories (narratives), which are composed of simpler ideas (memes, analogous to genes). Naturally, we tend to believe and communicate those narratives that suit our interests as status-seeking social primates. This tendency acts as a kind of meta-filter through which we digest the narratives we consume. Recall the words of Upton Sinclair:

“It is difficult to get a man to understand something when his salary depends on his not understanding it.”

Human organizations naturally craft narratives that suit their goals, such as expansion of influence. Contraction is never the goal, for the simple reason that organizations are composed of status-seeking social primates. Do you want to lose your job, get demoted, or have your budget slashed? I didn’t think so. You want to “achieve your goals,” “make an impact,” “serve your community,” and “fight for [Good Thing].” There are many euphemisms for status-seeking. It’s much less common to hear people communicate with nakedly self-interested language (“I just want more money,” “I’m just saying this to get laid”). We re-code our status-seeking into language that makes for a better narrative, one that’s more likely to be respected and therefore communicated by our peers.

The more an organization is respected, the more prestige it has. Expert credentials are a mark of prestige. Prestigious institutions acquire their status as such, in large part, through their association with experts. Harvard is a prestigious university. Lots of people want to get in, only a minority do. Lots of people care about what it’s faculty have to say and pay their attention when they speak, which is why Harvard is so influential. ADA is also influential. Many people take it seriously. We would therefore expect it to be composed of experts, the top experts when it comes to diabetes. Right?

ADA: Expert advice or misinformation?

Whether or not you believe ADA has been corrupted by its ties to corporate interests (more on that later), they presumably understand the basics of human metabolism. If their mission is to eradicate diabetes and they direct so many resources toward research and education, ADA presumably harbors bona fide diabetes experts. After all, they started out that way—founded by Dr. Mosenthal and other top physicians, back in 1939. ADA’s current employees may not all be doctors, but I would expect the staff responsible for educating people on diabetes to at least understand foundational concepts of metabolism.

After posting their “Plate Method” video online, ADA was flooded with comments. Many were critical. Before shutting off comments on their posts, they left this remark on the Facebook post featuring their Director of Nutrition & Wellness:

The comment seemed to be in response to the many people who stated that carbohydrates are not an essential part of the human diet. Essential dietary components are those we must eat in order to survive and function properly. For example, there are both essential and non-essential amino acids. The essential ones are those we must obtain through diet because our bodies cannot produce them. Vitamin C is another example. Unlike other animals, humans cannot produce vitamin C endogenously. We must therefore consume foods containing it.

Are carbohydrates essential components of the human diet? Here’s the key part of ADA’s response to the comments they received:

“The brain needs glucose to function appropriately, so a certain amount of carbohydrates is needed for people as part of healthy eating.”

As metabolic psychiatrist Dr. Georgia Ede explained, that statement is a half-truth. “A half-truth is a very powerful problem in the world,” she told me. The true part is that our brains do always need some glucose. At any given moment, brain cells use a combination of glucose (carb) and ketones (fat) for fuel. The exact mix depends on your diet and metabolic state, but some glucose is always there. The false part of ADA’s statement is that dietary carbohydrates are necessary for us to obtain glucose. That’s totally false and well-known. Through a process called gluconeogenesis, our cells can create glucose from non-carbohydrate substates. (I first learned this in Biochemistry 101, in college).

To recap: ADA posted their Plate Method video on social media. They got lots of critical comments, then posted a half-truth in response before shutting off new comments. Many were quick to point out these things. Some took time to politely critique their statement about the necessity of dietary carbs.

Who posted that factually inaccurate statement on ADA’s Facebook page, anyway? Was it Stacey Krawczyk herself, the Director of Nutrition featured in the video? Or was it just some social media manager? Whoever posted on behalf of ADA was either ignorant of gluconeogenesis or else knowingly posted a half-truth for other reasons. Either way, it’s misinformation.

That got me thinking: if ADA was founded by physicians well-versed in the biology of their day… who works there now?

Revolving Doors & Perpetual Pie

Because this article was first prompted by the uproar around ADA’s Plate Method video, I started by looking at their Director of Nutrition & Wellness. A registered dietitian with a Masters of Science degree in nutrition, she describes herself as a “wellness executive and food systems change agent”. Past employers include the National Soybean Research Lab and Kellogg Company.

One wonders: does Stacey believe soybean oil is a “good fat,” or that Kellogg’s breakfast cereals can be part of a healthy, balanced diet? Do her beliefs have anything to do with her work history? We can only speculate. What we know for sure is that Kellogg’s is publicly traded, so if she’s holding onto stock from her 7+ years of service she will benefit from an increase in the share price. She will also benefit if ADA grows and she’s able to move up through the ranks. If both things happen, win-win for Stacey.

What we’re getting at here is the concept of the “revolving door.” We see it all over. The most famous examples of revolving doors connect government to private industry—banking, pharma, and weapons manufacturers are infamous. Big Food is another. A revolving door is a mechanism by which interests are aligned across organizations that would otherwise be independent or even antagonistic to one another. Alignment happens organically as people move between organizations they have a financial interest in. No explicit, top-down coordination is required. If a bunch of people spend their careers going back-and-forth between banking and politics, this facilitates the creation of regulations that benefit the banks those individuals are moving to and from.

Revolving doors are not limited to government-private sector interactions. They can be found between private companies, research institutions, and non-profits. If you casually browse the “People” section of ADA’s LinkedIn page, you will see many such examples. People join and/or leave ADA to work in biotech or pharma companies making diabetes drugs, large food and beverage manufacturers, and other non-profit health institutions like the American Heart Association. Do these connections have anything to do with ADA’s designation of Cheerios as a “power snack?”

In addition to a Director of Nutrition who spent years at Kellogg’s, five minutes of searching revealed ADA executives who have worked as spokespeople for insulin makers like Eli Lilly and in sales at Coca-Cola. Analysis of publicly available tax documents has shown that the food industry donates a lot of money to US-based patient advocacy organizations. According to this study, nine food and beverage companies collectively donated over $10 billion inflation-adjusted dollars to such orgs between 2001 and 2018.

What are food companies really buying?

Why do large corporations, such as junk food makers, make such donations? What are they actually buying? According to Dr. Robert Lustig, they seek to exculpate themselves as causal forces driving obesity, metabolic syndrome, and other “disease of civilization.” For example, Coca-cola donated $1.5 million in 2015 to help start the Global Energy Balance Network, a non-profit that minimized the role of diet in driving obesity by overemphasizing physical activity. This narrative emphasis shifts blame away from food and beverage makers who load their products with high-fructose corn syrup and other obesity-promoting added ingredients. They want us to believe it’s all about energy balance (how much we eat) and energy expenditure (how much we move). Consumers should exercise more and watch their total calorie count, not focus on the specific ingredients engineered into processed foods.

An alternative narrative arises from the observation that obesity and metabolic dysfunction have continued to climb even though total calorie intake has been flat and people have been exercising more than they used to. If people’s metabolic health continues to decline despite these trends in energy intake and expenditure, it suggests a different story. Perhaps people aren’t just lazy. Perhaps our food supply is loaded with obesogens, substances that promote obesity and metabolic dysfunction independent of caloric content.

Narratives are powerful because they motivate human action. The stories we’re exposed to influence our choices. To the extent that you believe the narrative that metabolic health is primarily about how much you eat overall, your attention will focus more on the total number of calories you consume and burn, and away from the specific ingredients put into the foods you eat. To the extent you believe that specific foods should be avoided even in moderation, because they contain obesogens, you will be motivated to stop purchasing products produced by companies like Coca-Cola or General Mills. Which of these competing narratives you subscribe to determines your view of what constitutes a healthy “power snack.”

This is what I believe these companies are really buying with their donations to ADA, AHA, and other organizations: narrative selection. With respect to any set of human behaviors, there are always multiple competing narratives, each motivating us to act in certain ways. Organizations naturally seek to construct and promote those narratives that motivate people to act in ways that serve the interests of the organization. When General Mills donates money, they’re participating in narrative selection. And it works. The Tufts University “Food Compass” algorithm gives Cheerios a high score. That “evidence” supports ADA’s label of Cheerios as a, “Power Snack.”

The size of a company’s donations determines their ability to nudge these organizations in the direction of espousing Narrative A rather than Narrative B. If Splenda donates a million bucks and ADA’s Director of Nutrition has a problem with promoting Splenda-filled recipes to people, what should you do? If you want that sweet Splenda money to keep funding your stated mission, you fire the Director. (This is what a recent lawsuit settled by ADA alleged).

For an interesting exercise in how these relationships influence narrative formation, study the literature on the biological effects of Splenda, how that company responds in press releases, and their work with ADA promoting a certain narrative about “zero-calorie” sweeteners (which are not, in fact, devoid of calories).

“The purpose of a system is what it does.”

Whatever you believe about how and why ADA functions, it’s efforts to stop the spread of diabetes have not been successful. The organization is embedded in a complex network of organizations that play a role, directly or indirectly, in shaping the metabolic health of our society. This network is a complex system of interacting nodes, each comprised of human beings who (a) espouse the belief in mission statements, and (b) respond to quarterly incentives. Some of these mission statements, such as ADA’s, are explicitly aimed at eliminating diabetes. None would claim to be promoting the opposite. And yet, things aren’t moving in the direction of the stated mission. People act according to incentives, which tell us which way things will move.

A famous phrase from systems thinking is, “The purpose of a system is what it does.” It’s a simple heuristic used to explain why complex systems like human organizations often produce results at odds with the stated intentions of those who operate them. In analyzing complex systems, it tells us to focus on outcomes, not intentions.

Outcomes emerge from incentives, not intentions. Remember the cobras. When you feel motivated to grab your next power snack, ask yourself: what’s the story here, and who is telling it?

Special note: I contacted two ADA representatives ahead of producing this content, in order to hear their perspective. Stacey Krawczyk, Director of Nutrition & Wellness, did not respond through her personal website or LinkedIn. Chuck Henderson, CEO, told me, “My comms team will be in touch. They have your info.” I never heard from them.

To learn more about the topics covered in this essay, try these episodes of the Mind & Matter podcast:

M&M #132: Obesity Epidemic, Diet, Metabolism, Saturated Fat vs. PUFAs, Energy Expenditure, Weight Gain & Feeding Behavior | John Speakman

M&M #134: Omega-6-9 Fats, Vegetable & Seed Oils, Sucrose, Processed Food, Metabolic Health & Dietary Origins of Chronic Inflammatory Disease | Artemis Simopoulos

M&M #135: History of Diet Trends & Medical Advice in the US, Fat & Cholesterol, Seed Oils, Processed Food, Ketogenic Diet, Can We Trust Public Health Institutions? | Orrin Devinsky

M&M #140: Obesogens, Oxidative Stress, Dietary Sugars & Fats, Statins, Diabetes & the True Causes of Metabolic Dysfunction & Chronic Disease | Robert Lustig

M&M #100: Infectious Disease, Epidemiology, Pandemics, Health Policy, COVID, Politicization of Science | Jay Bhattacharya

For further reading:

Why Are We Getting Fatter? | Part I: Diet Advice, Health Trends & Informational Obesity

Good Carbs, Bad Carbs: How good is "good" when it comes to insulin?

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31000505/ -ADA Consensus on nutrition therapy

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33767525/ -Cost of different calorie sources

The ADA current consensus is that low-carb and very-low carb diets can be beneficial in cardiovascular disease. The difference being that the ADA recommends this as a valid option for nutrition, while the plate method is a piece of public health advice. This public health advice must be applicable to the most people and cause the least risk, and given the expense of replacing starchy staples (major source of carbs) with protein sources like meat and seafood, this cannot be applied to those who are at highest risk of diabetes, those in lower socioeconomic groups.