The Madness of Pop Psychiatry

“Call your doctor if you have fever, stiff muscles and confusion, which may signal a life-threatening condition."

I recently visited my grandmother. She’s frail, so we sat in the living room and watched network television. I didn’t notice the programming. Like carbon monoxide, it was tasteless and asphyxiating. I watched her consume an impressive sequence of pills while breathing oxygen through a plastic nasal cannula. She pulled them one at a time from a comically large color-coded pill box, transfixed by popular culture.

With the first commercial break my attention shifted to the TV. At least one third of the commercials I witnessed that morning were pharmaceutical ads. The one I noted was for a drug called Rexulti®.

My elderly grandma has dementia. She does not take Rexulti®. That’s good news because, as the commercial informed us, this drug poses an increased risk of death or stroke for her demographic.

For those not elderly and demented, side effects can include fever, stiff muscles and confusion. As the voice actor made clear, you should call your doctor if you experience this trifecta, “which may signal a life-threatening condition.” There’s also increased cholesterol, weight gain, high blood sugar, decreased white blood cells, compulsive behaviors, dizziness, seizures, and uncontrollable muscle movements (which may be permanent).

Given this list of occasionally life-threatening and sometimes irreversible side effects, what underlying condition would you guess Rexulti® is meant to treat? Go with your gut, then listen to this 60-second Rexulti® commercial:

As with many pharma ads, this could be easily mistaken for sketch comedy. Rexulti® is a depression drug. More specifically, it’s an adjunctive depression drug—you take it in addition to whatever antidepressant you’re already taking, if that one just isn’t cutting it.

Let’s explore a plausible scenario for how Rexulti® woman became depressed, got her Rexulti® prescription, and what’s in store if she continues with the prescription drug strategy that popular culture, and her doctor, have recommended. Along the way, we will note what these psychotropic drugs are doing in her brain and what side effects they might be causing. Eventually, we will contemplate an alternative diagnosis.

(Please note: Although I am a doctor, I’m not that kind of doctor and none of this is medical advice.)

To make this story more relatable, let’s give Rexulti® woman a name: Karen.

SSRIs, Chemical Imbalances & Depression

For the roughly 1 in 10 Americans with depression, the go-to prescription a doctor will write is for a Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitor (SSRI). A famous example is sertraline (brand name: Zoloft®), which could easily be what Karen was already taking.

SSRIs work by elevating serotonin levels. The idea here is that normal people have a certain “balance” of neurotransmitters sloshing around their brain, endowing them with normal feelings. If that’s how things actually worked, we could think of psychiatric illness as a chemical imbalance within the brain. For example, if depression was caused by having too little serotonin floating between your synapses, an SSRI could correct the imbalance.

And because the word “selective” is baked into the name, that must mean SSRIs are selective for serotonin reuptake and do not impact other neurotransmitter systems, right? Well, no. Like the TV commercials, the naming of these things is a marketing function. But the name stuck and it influences popular thinking.

Below is the original Zoloft® commercial, which helped popularize the “chemical imbalance mindset.” This heuristic permeates medicine to this day. Words like “mindset” and “heuristic” work well here because this is a commonly held, intuitive conception of how the brain works. It is not a rigorous and empirically grounded scientific theory. It’s “pop psychiatry.”

SSRIs are part of the standard treatment for major depressive disorder (MDD, or simply “depression”)—a psychiatric illness which can be informally described as feeling like the cartoon blob in the Zoloft® commercial. Since the 1990s, tens of millions of Americans have been taking one or more antidepressants each year. The number of such patients more than doubled from 1996 to 2015. It’s even higher today.

Because we’re talking about using psychoactive drugs to treat psychiatric illness, it’s natural to assume all of this requires the expertise of psychiatrists—doctors with specialized medical training in disorders of the mind. This would mean that the reason tens of millions of people are on SSRIs is because each has been carefully diagnosed by a specialist as having depression or a related mental illness.

That is not how it works.

To get SSRIs you pretty much just need to tell whatever kind of doctor you see that you’ve been sad for a couple weeks. Antidepressants are prescribed at high frequency, with ~80% of scripts written by general practitioners, not psychiatrists. Here’s data from the UK, highlighting the historical growth of SSRI prescriptions compared to other antidepressants:

General practitioners are primary care physicians—generalists, not specialists. An optimist might say that their expertise is broad, stemming from a wide-ranging interest in health and medicine. A cynic might say their expertise is shallow and that they don’t really know how most prescription drugs work—at least not in detail. They just know what brand names to prescribe when they hear patients regurgitate strings of words that popular culture uploaded to their brain.

Have you ever witnessed a pharma ad that doesn’t end with, “Ask your doctor…”? Of course not. Good consumer marketing requires a clear call to action.

When prescribed an SSRI, you need to have patience. For those people who experience an SSRI mood boost, this usually takes ~6-8 weeks to settle in. If a few weeks go by and you’re not feeling better, the default next step is simply to increase the dose. This might help, but it will also increase the risk of unwanted side effects.

If your Zoloft® doesn’t work after one or two dose adjustments, the next step is to try a different SSRI. Or another (there are many). Or a Selective Norepinephrine Inhibitor (SNRI). If none of those help, you may have treatment-resistance depression. In practice, this means you probably tried at least a couple different drugs at a couple doses each over a period of several months.

This is what happened to Karen and where an adjunctive drug like Rexulti® comes in.

What Kind of Drug is Rexulti®?

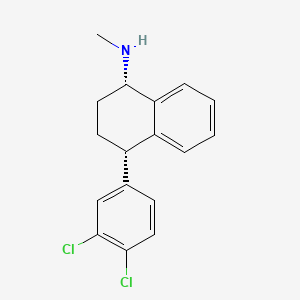

Rexulti® is the brand name for brexpiprazole, which belongs to a class of drugs known as antipsychotics. These drugs impact dopamine D2 receptors, a specific type of dopamine receptor in the brain. While these receptors are a major site of action, they are not the only site of action. As with most brain drugs, the pharmacology of Rexulti® is complex. Rexulti® modulates both dopamine and serotonin transmission.

But wait, Karen has depression. She’s not psychotic… is she? Why would someone with depression take an antipsychotic?

To try to understand this, let’s look at what antipsychotics are traditionally used for. By understanding how antipsychotics work and are used in modern medicine, a clear and logical picture for why they make sense for depression should emerge… right?

Psychosis & The Effects of Antipsychotics

Under different circumstances, an antipsychotic like Rexulti® would be used to treat psychotic disorders like schizophrenia. People experiencing psychosis are out of touch with reality in some way. They might experience extra perceptual phenomena, such as auditory hallucinations (“positive symptoms”). They might lack normal levels of human desire, such as being unmotivated or apathetic (“negative symptoms”). Most people with schizophrenia have a mix of both positive and negative symptoms.

Historically, some of the first drugs used to treat psychosis were “typical antipsychotics,” such as haloperidol (brand name: Haldol®).

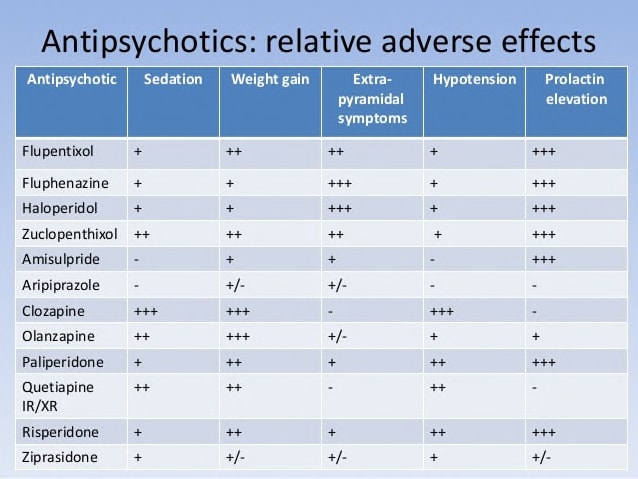

These antipsychotic drugs have not only been used to treat chronic forms of psychosis, but to ameliorate acute psychotic episodes like those triggered by hard street drugs. Antipsychotics like Haldol® act a tranquilizers, dampening many psychotic symptoms. Side effects may include: involuntary movement disorders, impotence, weight gain, and metabolic syndrome. Not fun.

Like antidepressants, there are many antipsychotics. Newer antipsychotics were developed for the same reason “next generation” antidepressants like SSRIs were—an attempt to find drugs that provide symptom relief with a more tolerable side effect profile. Rexulti® is one of these next-generation antipsychotics.

What do these drugs feel like?

Here’s a video from a woman with schizoaffective disorder, which is sort of like a cross between schizophrenia and depression. It’s ~12 minutes long, so I’ve quoted key portions below which are relevant to Karen’s story.

After trying multiple antipsychotics, here’s her summary of the major side effect (lightly edited):

The biggest side effect is kind of like a “numbing.” You feel like there’s a barrier between what you know you’re capable of feeling and what you [feel] on the medication. I’ve had it to varying degrees with different [antipsychotics] but it’s a common thing. To some extent, you’re going to feel some degree of “numbing.” [You should] seek out rich experiences that you can feel something with, because the numbness can really get to you and I think that’s a side effect that a lot of people really struggle with.

There are other side effects, including weight gain and tardive dyskinesia (TD). She describes TD as, “involuntary movements of the tongue, lips, and face caused by prolonged use of antipsychotic medications.” Recall that one of the side effects mentioned in the Rexulti® commercial was uncontrollable muscle movements. That’s dyskinesia.

Unwanted side effects must be weighed against a drug’s ability to reduce symptoms. Someone with a psychotic disorder will likely need to try multiple antipsychotics at different dosages to manage tradeoffs between symptom relief and side effects. For many, symptom relief does not outweigh the side effects, which is why treatment non-adherence rates are roughly 50% for schizophrenia.

What about the “negative symptoms” of psychosis? The woman in the video above describes these as symptoms that “look more like depression—things like lack of motivation, lack of pleasure in things, lack of focus.”

Okay, so here’s a connection to depression: the negative symptoms of psychotic disorders overlap with the symptoms of depression. If antipsychotic drugs are good at treating depression-like symptoms in people with psychotic disorders, it’s natural to suppose they might also help someone with depression.

Here’s the problem: antipsychotics are generally not good at treating these negative symptoms. They are typically better at treating the positive symptoms (e.g. hallucinations). So why would we expect these drugs to work well for people with treatment-resistance depression?

I don’t have a good answer for you. And neither does Karen’s doctor, who is a general practitioner. All I can say for sure is that, because Rexulti® is indicated for treatment-resistance depression, these things must be true:

A lot of money was spent running clinical trials to see if Rexulti® performs better than placebo for treatment-resistant depression.

The United States Food & Drug Administration (FDA) was satisfied with the data produced by these studies and approved Rexulti® for this indication.

Money was spent creating Rexulti® commercials.

The makers of Rexulti® made sure to send representatives to educate doctors about what this FDA-approved drug should be prescribed for.

The point is that Rexulti® checks all of the boxes it needs to check, so Karen’s doctor prescribed it.

Fun fact: everything in the Rexulti® commercial is based on two 6-week studies. The FDA does not require drug companies to submit ads to any kind of approval process before they go live.

Based on everything we’ve learned so far, let’s reconstruct a plausible path by which Karen got from the beginning of her depression to the end of the Rexulti® commercial. We’ll then consider how Karen might be responding to her new meds after some time has passed and what her next steps might be.

Karen’s Mental Health Journey: Part I

Like everyone else, Karen uses social media to share her life with friends and family. This mode of social interaction makes it easy for her to engage in frequent interpersonal comparisons. She frequently looks a photos, infers how other people felt in them, and contrasts that with her present mood. She always smiles for photos, even when she doesn’t feel totally happy.

At some point, Karen began feeling depressed and didn’t know why. She wasn’t feeling the way she imagined she should feel. She mentioned all of this to her family doctor, who is not a psychiatrist. Having heard stories like this many times before, her doctor prescribed an SSRI.

Karen started on fluoxetine (brand name: Prozac®). 20 mg daily for a few weeks. At follow-up, she reported that she could sort of feel the medicine but still felt depressed. She was bumped up to 40 mg. This still didn’t make her feel the way she wanted. Plus there were side effects (awkward bathroom- and bedroom-related issues).

Karen’s doctor reassured her. This happens all the time. Everyone is different and there are many different antidepressants. With a little trial-and-error, they would find the right medication for Karen.

Her doctor next prescribed Zoloft®. 50 mg once daily. For several more weeks, it elevated Karen’s serotonin levels. Despite the shift in brain chemistry, Karen still wasn’t happy—not truly. Her dose was increased to 100 mg.

Karen felt like a phony. She may have looked happy in her Facebook photos, but she didn’t feel happy when she looked at them. Noticing this mismatch made her feel anxious. Because she looked at photos of herself often, she felt this way often.

This is where Karen was at the beginning of the Rexulti® commercial.

Karen’s doctor knows that SSRIs increase serotonin levels in her brain. Because that isn’t working, perhaps there are additional brain chemicals that are out of balance? Like a home stereo, maybe the music will sound better if we turn up the bass and adjust the treble?

Lucky for Karen, a pharmaceutical representative shared this intuitive metaphor with her doctor during a recent visit. This allowed the doctor to deliver the good news to Karen, with supporting statistics from the digital brochure the pharma rep provided: "When added to an antidepressant, Rexulti® is proven to reduce depression symptoms 62% more than the antidepressant alone."

(Because there is at least one positive clinical trial result, the FDA allows the word “proven” to be used in marketing materials.)

With this prescription upgrade, Karen added once-daily Rexulti® (3 mg) to her drug regimen. Within a few weeks, Karen was feeling better. The Zoloft®-Rexulti® combination worked. “Now when I say ‘Good times,’ I mean it!”

The commercial ends with Karen and her friends happily walking out of cooking class. It’s a beautiful summer day and the narrator delivers a clear call to action—“Talk to your doctor about adding Rexulti®.”

A few months go by.

Karen’s Mental Health Journey: Part II

Karen is still feeling better on her daily Zoloft®-Rexulti® combo. Some minor side effects have developed, but nothing drastic. She put on a few pounds, which can happen with antipsychotics. Her sex drive was lower. As a middle aged married woman with a gym membership, it’s not a big deal—a fair price to pay for happiness.

But there has been another, weirder side effect developing. Every day, from time to time, Karen’s hands and facial muscles… move. Spontaneously. People notice, which is embarrassing. She used to be self-conscious about her depressed mood. Now she’s self-conscious about her uncontrollable movements. Naturally, she turns to her doctor.

Fortunately, this is a known problem. We mentioned it above while exploring antipsychotic drugs. Karen has tardive dyskinesia, which ~20-30% people taking these meds experience. The Rexulti® commercial warned of this: “Side effects include… uncontrollable muscle movements (which may be permanent).”

Her doctor reassures her. Dyskinesia has a simple fix: another adjunctive drug.

If you liked the Rexulti® commercial, you’re going to love this one. Pretend it’s the same actress who played Karen in the Rexulti® commercial:

Walk toward to light, Karen. Do not operate heavy machinery. This one can make you sleepy. Valbenazine (brand name: Ingrezza®) is a vesicular monoamine transporter 2 inhibitor. Take it with your dopamine D2 receptor partial agonist and it may reduce your tardive dyskinesia.

Other than drowsiness, possible side effects include, “potential heart rhythm problems and abnormal movements.” Wait—abnormal movements? Isn’t that what Karen is trying to treat? The commercial doesn’t elaborate. I don’t have a good answer for you either. There must be other kinds of abnormal movements. Perhaps they’re less noticeable, or maybe there’s a pill for that?

Karen is now taking three drugs. The antipsychotic apparently boosts the effect of the SSRI (sometimes), which doesn’t help on its own. The third drug treats the uncontrollable muscle movements caused by the antipsychotic, but may itself cause abnormal movements. She is a bit heavier, less sexually active, and a little drowsy. Her heart rhythms look fine but the doctor is going to keep an eye on it, just to be safe.

Karen may not enjoy these side effects, but hey, she’s feeling better. Her daily drug cocktail allows her to continue living life exactly as she had been while she was depressed, minus the low mood. She no longer feels that worrisome mismatch when she looks at photos of herself on Facebook, which she continues to do often.

Is it just me or does something about this seem a little… insane?

“Insanity is doing the same thing over and over…“

Recall where the Rexulti® commercial begins: Karen is staring into Facebook, listening to a voice in her head. It’s her ego—the narrative voice chirping away within each of us, rationalizing our perceptions. Unlike a schizophrenic, she is not misperceiving the voice as coming from a separate, fictional entity. Nonetheless, she listens to it. She takes it seriously.

At the start of the commercial, Karen is engaging with social media and feeling bad while doing so. She probably does this often. Performing an action repetitively, even if it doesn’t lead to reward or pleasure, is the definition of compulsive behavior. We all know that compulsive liking on Facebook is common. The Rexulti® marketing team presumably wrote the script this way because it’s so relatable.

The commercial ends the way it started: with Karen liking photos on Facebook while her ego narrates. According to this inner voice, she no longer feels sad while doing this. What’s noteworthy to me, and captures something about the “crazy times” we’re living through, is that her behavior has not changed. She appears oblivious to the very real possibility that her behavioral choices contribute to her psychological distress.

At this point, I’m reminded of the common refrain, “Insanity is doing the same thing over and over and expecting different results.” Karen’s dual-drug combination has allowed her to continue engaging in the same behaviors over and over while blunting the emotional distress formerly associated with it. She may not have full-blown psychosis, but she is disconnected from reality in this way.

As it turns out, another side effect of Rexulti® is compulsive behavior. Is it possible that her prescription drugs are not only masking her depressed mood, but simultaneously reinforcing the compulsive behavior she was engaging in all along? Who knows. These ads are so self-evidently wacky that there’s little value in deconstructing them further.

At this point, Karen has been on her antipsychotic for months and SSRIs for over a year. Let’s just wish her well and hope there are no long-term ill effects.

Chronic Use of Antipsychotics & SSRIs

Karen is a white, middle-aged woman. In the US, this demographic has the highest rate of long-term antidepressant use by far. As of 2014, around nine million woman aged 45+ had been using antidepressants for at least five years:

In terms of long-term side effects, let’s start with her adjunctive drugs, then move on to SSRIs.

We’re already familiar with two long-term side effects of Rexulti®: weight gain and uncontrollable movements. Remember, these abnormal movements can become permanent. This was the reason Karen started using Ingrezza®, which apparently reaches maximal effectiveness at 32 weeks, requiring at least 6-8 weeks for “significant effects” to be seen.

What about SSRIs? They have been used widely for decades, with many millions of people taking them for years. It’s worth stating up front that it’s inconceivable that the chronic use of a psychoactive drug like this wouldn’t have a lasting impact on the brain. Let’s consider some possible long-term effects at a high level.

Like many other psychoactive drugs, SSRIs can cause dependency. Dependency is distinct from addiction, involving the development of withdrawal symptoms following discontinuation of a drug after extended use. Addiction, in contrast, is the compulsive consumption of a rewarding drug despite negative consequences. Some drugs can be addictive and cause dependency (e.g. opioids). Others can be addictive without causing dependency (e.g. cocaine), while others can cause dependency without addiction (e.g. caffeine).

While SSRIs can cause dependency, they are not addictive. A good common sense test for a drug’s addictive potential is to ask how many people go out of their way, and spend a significant portion of their income, to obtain it. No one is buying SSRIs on the street, or re-selling their prescription. Still, dependency is a concern. It is more common if someone abruptly stops using or they have been taking it for a very long period of time.

The presence of dependency is itself evidence that the brain has “gotten used to” a drug. In Karen’s case, she has been exposed to elevated serotonin levels for over a year. This has likely stimulated growth of new connections and caused neurons to decrease the number of serotonin receptors they express, in order to compensate for the extra serotonin floating around. If she suddenly stops taking her SSRI, many of these changes will no longer be ideal as her serotonin levels decline. As a result, her brain circuits need to adapt to this change, a process which can manifest in withdrawal symptoms.

Symptoms of “SSRI discontinuation syndrome” can include sensory and gastrointestinal issues, dizziness, lethargy, sleep disturbances, anxiety, irritability, and poor concentration. The sleep issues are interesting given that SSRIs are known to suppress Rapid Eye Movement (REM) sleep, which is the phase associated with vivid dreaming. The long-term effects of REM sleep deprivation are difficult to study, but there is some reason to believe this could have consequences for the learning & memory functions.

The short-term side effects of SSRIs are also likely to persist as long one is taking them. Karen experienced some of the more common ones: weight gain and sexual dysfunction. While there is some evidence that sexual difficulties can endure even after SSRI discontinuation, I found the literature on the long-term and permanent effects of SSRIs to be quite sparse (at least for human studies).

As a neuroscientist, I would suggest following common sense here. The more frequently and chronically someone uses a psychoactive drug, the more likely it is that their brain will undergo permanent changes that persist in the drug’s absence. This won’t necessarily be a bad thing—there might be persistent beneficial changes.

We also have to consider the incentives that determine what gets studied, by whom, and for how long. Drug manufacturers have strong incentives to demonstrate, as quickly as possible, that a drug provides some symptom relief in the short-term (days or weeks). They have little incentive to conduct longer-term studies, which will naturally be more expensive and always have the potential to reveal an inconvenient truth.

Given that these drugs can require dozens of weeks before symptom relief might occur, and that they are increasingly prescribed for many years, one has to wonder: is this really the best we can do? Ideally, we would have treatment options for depression and other psychiatric conditions that help direct the brain to “heal itself” without the need for chronic drug consumption.

Is that even possible?

Chemical Re-Balancing vs. Circuit Re-Wiring

One of the most exciting areas of research in neuroscience and psychiatry today involves a class of drugs called psychoplastogens. This is newly-minted term refers to drugs that can rapidly induce structural neuroplasticity—the physical rewiring of connections between brain cells.

SSRIs are themselves capable of stimulating neuroplasticity in the brain, but this typically takes several weeks to manifest and is thought to be why it often takes several weeks before patient’s report any benefit. In contrast, psychoplastogens induce plasticity rapidly. Indeed, new connections can sprout overnight. Neuroscientists can even watch this happen in the brains of lab animals (jump to 7:38 for the most relevant part):

Another interesting thing about psychoplastogens is that most of them are strongly psychoactive. They include everything like classical psychedelics (e.g. psilocybin, LSD, DMT) to dissociative drugs like ketamine and ‘empathogens’ like MDMA. I have discussed these drugs elsewhere. They have been used in clinical trials to treat, and sometimes even cure, everything from PTSD to addiction and treatment-resistant depression.

Perhaps most remarkable of all is that they exert therapeutic effects after a small number of doses—sometimes just one. Often used in conjunction with psychotherapy, they represent a different kind of treatment mindset. By taking a small number of psychoplastogen doses, the brain is temporarily put into a state of heightened malleability—new connections can be made or broken with greater ease. The work done in psychotherapy, and through conscious behavioral changes made by the patient, is then better able to take root in the person’s brain. When the ‘window of plasticity’ closes, these positive changes get locked into place. Benefits can persist without chronic drug intake.

It’s crucial to emphasize the role of consciously made behavioral changes. This is what psychotherapy helps motivate, and what the content of psychedelic trips often inspires. If insanity is doing the same thing over and over again and expecting different results, then a key part of the problem is behavioral—new results will only come as a consequence of new behavior. In this way, behavior is viewed as upstream of mental health outcomes. This is the opposite of Karen’s drug strategy. She is taking prescription drugs to boost her mood while she continues doing all of the same things she was before.

The basic idea here is to re-wire brain circuits in a relatively short time period, using a limited number of drug doses. This stands in stark contrast to the strategy that Karen and millions of other people have taken. Karen’s doctor is effectively trying to fine-tune the balance of neurotransmitters in her brain and is willing to do this for years if there is symptom relief. If side effects arise, then adjunctive drugs are simply added as needed.

The Pop Psychiatry Mindset

By ‘pop psychiatry,’ I mean depictions of psychiatric treatment coming to us through popular mass media, created for consumer marketing purposes. The drug commercials embedded in this essay are examples. They are not created by the pharmacologists who study the mechanisms of action, or the doctors who prescribe them—they are created by marketers, with the ultimate goal of driving sales. They are not so much about knowledge transfer as they are calls to action. Education is incidental.

This is easy to see if you simply listen to what they say. Take this part of Ingrezza commercial, for example:

Some meds for mental health can cause abnormal dopamine signaling in the brain. While how it works is not fully understood, Ingrezza is thought to reduce that signaling.

What they’re saying is that they don’t really know what’s going on with this drug. Other than using motion graphics to communicate that the drug will do something in your brain, the Ingrezza® commercial makes it clear that you should be able to stay on your current dose of other mental health meds. It’s simple. It’s easy. You just have to ask your doctor, and the light of heaven will shine upon you, just like Karen.

This general mindset is pervasive: If you’re feeling bad, or your life is somehow uncomfortable, you should ingest medication to blunt those feelings. And that is, quite literally, what some of these drugs do—they blunt feeling. Recall the primary side effect described in our discussion of antipsychotics: “[It’s] like a ‘numbing.’ You feel like there’s a barrier between what you know you’re capable of feeling and what you [feel] on the medication.”

Feeling is information. When we feel bad, our body is communicating something. It’s telling us that something needs to change. If we simply blunt that feeling, we blunt the signal to change. Consider a simple case of physical pain, such as placing your hand on a hot stove. It hurts! That feeling means stop doing that.

We can’t learn without pain. —Aristotle

We need to feel emotional pain just as we need to feel physical pain. In rare cases, people are born with genetic mutations that prevent them from feeling pain. That might sound desirable, until you learn the devastating consequences. Without the ability to feel pain, such people have diminished ability to learn how to act in ways that preserve their physical health. They fail to learn to keep their hand off of the stove, so they keep getting burned.

And this, I think, is what is happening to Karen. She is blunting her ability to feel emotional pain. She is treating her ability to feel the burn rather than learning not to touch a hot stove. Maybe for Karen the hot stove is her social media habit, or listening too much to the voice in her head. Maybe it’s a whole bunch of things. But if she doesn’t change her behavior, she should be prepared to stay on her meds for years to come, just like millions of other people.

The pop psychiatry commercials always depict medicating as idyllic. They emphasize words like “simple” and “easy.” Just one pill, once a day. Ask your doctor. You don’t have a change anything about your lifestyle. These drugs are something you supplement your existing lifestyle with, like a vitamin. Such messages, repeated over and over through mass media, take root in people’s minds. This is one way culture is created.

Is this culture healthy? Is it sane?

I discovered the Ingrezza® commercial because The Algorithm recommended it me after I re-watched the Rexulti® commercial. I started seeing pharma ads on my own social media feeds, remembering how common they were on the network television stations I encountered while traveling. What if these became a part of my daily life? Would it start to seem less creepy? Would I eventually ask my doctor?

I thought about how many people there must be absorbing these messages through screens, day after day. I thought about my grandma.

To learn more about the topics covered in this essay, try these episodes of the Mind & Matter podcast:

David Olson: Psychedelics, Psychoplastogens, Microdosing, Mental Health, Brain Chemistry, Creating Novel Drugs | #46

Karl Deisseroth: Psychiatry, Autism, Anxiety, Depression, Dissociation & "Projections: A Story of Human Emotions" | #35

Lisa Monteggia: Ketamine, SSRIs, Depression, Psychiatric Disorders & the Brain | #29

This is a great take on the inside down state of the pharmaceutical industry. Add in PBM’s and insurers and we have the most profitable healthcare system in the world.

This is a really interesting, well considered piece of writing- thank you for sharing it. I’m going to have to read it again to take it all in.

Direct to consumer advertising of prescription drugs isn’t legal in Australia, and for that I’m grateful. However, the same messages have still been coming through peer to peer interactions social media which I think is also challenging.

I think it’s so important for consumers to be informed but that needs to include maintaining a healthy level of scepticism regarding the information sources. I think this applies to all drugs- prescribed or otherwise.

Thanks again, you’ve given me something to think about.