Worth the Trip: Psychedelics as an emerging tool for psychotherapy

What are psychedelics and why is everyone talking about them?

As your eyes close, a kaleidoscopic vision engulfs your entire field of experience, filled with pattern, color, and sense of deep meaning. Thirty minutes ago you were given a controlled dose of a potent, and illegal, hallucinogenic compound—all in the name of science. Months from now, you will say that this was one of the most profound experiences of your life.1 You have joined a small but growing number of human subjects participating in an exciting new wave of research. The aim of this work is to understand how an infamous class of mind-altering substances—psychedelics—may actually be a powerful tool for treating certain forms of psychological suffering.

Psychedelics are a special class of substances known for the vivid perceptual and cognitive changes they induce. Most are classified as Schedule I controlled substances. Legally, this means the U.S. federal government believes they have a high potential for abuse, no currently accepted medical use, and are unsafe to consume even under medical supervision. Despite this legal classification, a variety of psychedelics are currently being studied in laboratory and clinical settings. The results of this research suggest that they are non-toxic, pose no significant risk of dependence, and show great promise in treating a variety of psychiatric ailments.2

How do they actually exert their effects in the brain?

What do psychedelics actually do?

Classical psychedelics include, psilocybin, a molecule found in a variety of fungi (“magic mushrooms”), lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD), originally synthesized from components of a wheat fungus, and dimethyltryptamine (DMT), an especially potent psychedelic produced by many plant species. The chemical structures of these compounds resemble serotonin, an important chemical messenger in the nervous system (Figure 1). One of their primary effects is to stimulate neurons in the brain that are naturally responsive to serotonin. These serotonin-sensitive brain cells are widespread in the wrinkly outer layer of the brain known as the cerebral cortex. The cortex is disproportionately large in humans compared to other mammals, and is widely believed to enable many of our higher cognitive abilities.

Although psychedelics typically share similar chemical properties, the effective doses, routes of administration, and duration of their effects vary dramatically. The subjective effects also depend strongly on a person’s environment and expectations.3 At low to moderate doses these typically include mild to moderate distortions in cognition and sensory perception. At higher doses, profound, life-altering experiences are reported, often described as having a mystical or transcendental character.4

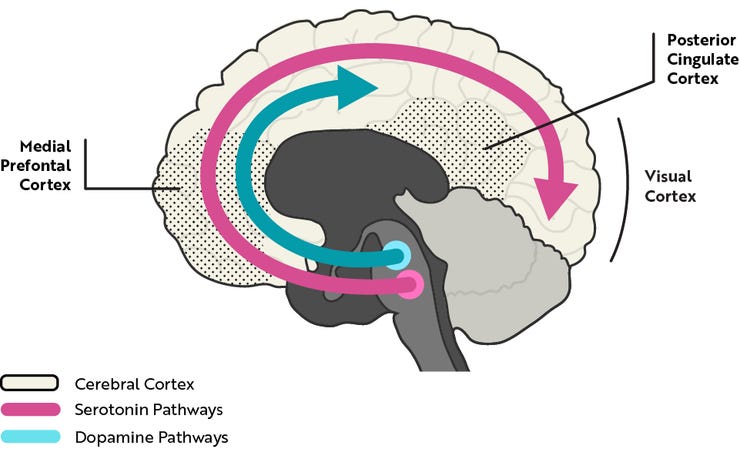

Unlike psychedelics, drugs of abuse such as cocaine, methamphetamine, and nicotine strongly stimulate the brain’s dopamine system (Figure 2), which is critical for their habit-forming potential. The ability of psychedelics to act primarily on the serotonin system is thought to be important for their unique subjective effects and negligible habit-forming potential. Preventing their ability to stimulate serotonin-sensitive neurons also prevents their hallucinogenic effects.5 But what is going on in the brain as a whole during the psychedelic experience? In just the past few years, the tools of modern neuroscience have allowed researchers to begin to answer this question.

Psilocybin: effects on brain activity and conscious experience

Neuroscientists have recently studied the effects of psilocybin on the brain activity of healthy human participants.6 They found that psilocybin caused changes in activity across the entire cerebral cortex. These changes were especially pronounced in areas of the cortex that make up the “default-mode network.” The default-mode network is composed of a group of brain areas most active when we are not actively engaged in a task, and is thought to be important for aspects of cognition such as introspection, mind-wandering, and self-referential thought.

Another study using functional brain imaging also found psilocybin-induced changes in brain activity.7 In particular, they observed that psilocybin led to decreased activity in several brain regions, with some of the largest decreases in default-mode areas like the medial prefrontal cortex and posterior cingulate cortex (Figure 2). These same brain regions contain many of the serotonin-sensitive neurons that psychedelics interact with, and show increased activity during self-related thinking under normal conditions. Could one of the major effects of psilocybin and other psychedelics be to decrease activity in certain brain regions, thereby changing the very sense of self that typically frames our everyday conscious experience?

Intriguingly, default-mode areas also become less active in other altered states of consciousness, such as meditation.8 Indeed, people often use similar language to describe the psychedelic experience and non-ordinary states of consciousness like meditation and sensory deprivation.910 These include experiences of depersonalization, frequently verbalized in terms of “ego disintegration,” “boundlessness,” or the feeling that all things are intimately connected. Meditation and sensory deprivation have also been implicated as treatments for depression and anxiety [16], which is an area where psychedelics like psilocybin show great promise.

Psychedelic psychotherapy

Psychedelics (mainly LSD) were originally studied in the mid-twentieth century, and had shown promise in treating alcoholism and end-of-life anxiety.11 The original impetus for this research came in part from psychiatrists’ own experience with these substances, and the idea that they might work by allowing patients to see their condition from a new perspective.12 But after passage of the US Controlled Substances Act in 1970, research halted. In the past several years, however, the potential therapeutic applications of psychedelics have once again become an active area of research.

Psilocybin was recently given to healthy volunteers in order to study its acute and long-lasting effects. The main finding was that, in most people, psilocybin could induce highly profound, “mystical-type” experiences. In interviews and questionnaires administered after these sessions, participants rated their psilocybin experiences high in qualities such as ineffability (difficult to describe in words), unity (feeling that all things are connected), and having a deeply felt positive mood. Two months after these sessions, the vast majority of participants rated their psilocybin experience as one of the top five most meaningful experiences of their life and as having increased their sense of well-being and life satisfaction. To help put things into clearer perspective, participants sometimes compared the significance of their experience to the death of a parent, or birth of their first child.

Psilocybin has also been administered to terminally ill cancer patients with the hope of alleviating their psychological distress. For many people, learning of a terminal diagnosis can lead to debilitating depression and anxiety. An initial study demonstrated that psilocybin could be safely administered to such patients without inducing adverse effects.13 Cancer patients in a more recent study at NYU Medical School have seen dramatic and long-lasting reductions in depression and anxiety. Remarkably, these effects were achieved after just a single dose of psilocybin, and it is astounding to hear personal testimonies from patients:

“I don’t think I’ve experienced—ever—the gratitude that I felt. Gratitude for what? It was just gratitude. I don’t like to talk about it, because it’s really beyond words.”

A major theme of this research so far is that psilocybin can, under appropriate conditions, reliably induce profound and potentially life-altering experiences; it seems to be able to change brain activity in ways that radically shift our sense of self, reinforcing the original intuition that psychedelics may help reframe a person’s typical thought patterns. “Cognitive reframing” is a common strategy in traditional psychotherapy, and psychedelics may provide a means for kick-starting the reframing process. In the words of one researcher, “individuals transcend their primary identification with their bodies and experience ego-free states [during the psychedelic experience]… and return with a new perspective and profound acceptance.” In this spirit, pilot studies investigating the potential use of psilocybin as an addiction therapy aid have been very encouraging, with success rates as high as 80% in an initial smoking cessation study, and larger studies currently underway.14

Despite a variety of promising results, researchers urge extreme caution. They stress that this area of research in its infancy, and that experiments have been conducted under carefully controlled, comfortable, and supervised conditions. Disturbing psychedelic experiences (“bad trips”) have been reported by recreational users and participants in psychedelic research are carefully screened for mental health issues before being selected. Nonetheless, there is optimism that psychedelics may one day become part of the legal psychiatric toolkit. More research is sorely needed, and some researchers have recommended that the federal government reclassify these substances in order to facilitate future efforts. No matter what the future holds for the place of these substances in society, the work currently being done suggests that, for some people, the psychedelic experience may be well worth the trip.

A version of this article originally appeared elsewhere.15

Interested in learning more about psychedelics? Try these Mind & Matter episodes:

Brian Muraresku: Psychedelics, Civilization, Religion, Death & Plant Medicine | #1

Charles Nichols: Psychedelics, Inflammation & New Psychedelic Drugs | #2

Hamilton Morris: Drugs, Society & Hamilton's Pharmacopeia | #6

“Blisshrooms.” (2012). Radiolab.

Nichols, D.E. (2004). Hallucinogens. Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 101, 131-181.

Psychoactive Basics. Erowid.

Griffiths, Roland (2009, November 9). TEDxMidAtlantic.

Nichols, David (2011, January 6). David Nichols – Psychedelic Science.

Muthukumaraswamy, S.D., et al. (2013). Broadband Cortical Desynchronization Underlies the Human Psychedelic State. J. Neuroscience. 33(38):15171-15183.

Carhart-Harris, R.L., et al. (2012). Neural correlates of the psychedelic state as determined by fMRI studies with psilocybin. PNAS. 109(6):2138-43.

Brewer, J.A., et al. (2011). Meditation experience is associated with differences in default mode network activity and connectivity. PNAS. 108(50):20254-9.

Sensory Deprivation Tanks. Vice. (2013, April 30).

Harris, Sam (2007, January 8). Selfless Consciousness Without Faith. The Washington Post.

Costandi, Mo (2014, September 2). A brief history of psychedelic psychiatry. The Guardian.

Slater, Lauren. (2012, April 20). How Psychedelic Drugs Can Help Patients Face Death. The New York Times.

Magic Mushrooms and the Healing Trip. The New Yorker (2015).

Johnson, M.W., et al. (2014). Pilot study of the 5-HT2AR agonist psilocybin in the treatment of tobacco addiction. J. Psychopharmacology. 28(11):983-992

Jikomes, Nick (2015, March 2). Worth the trip: psychedelics as an emerging tool for psychotherapy. Harvard University SITN.