Trusting the Science: Do Diet Researchers Know What's in the Diets They Research?

Diet research is filled with poorly controlled studies, misprinted diet information, and irreproducible methods.

Not medical advice.

"The first principle is that you must not fool yourself, and you are the easiest person to fool."

—Richard Feynman

When children first learn about science in grade school, they’re taught the importance of changing only one variable at a time. You isolate and manipulate a single variable of interest, holding everything else constant. In the modern adult world, professional scientists routinely fail to do things this way, allowing multiple factors to vary between conditions, often without even knowing exactly what all those variables are. Experiments are poorly controlled, and researchers don’t even realize how poorly controlled they are.

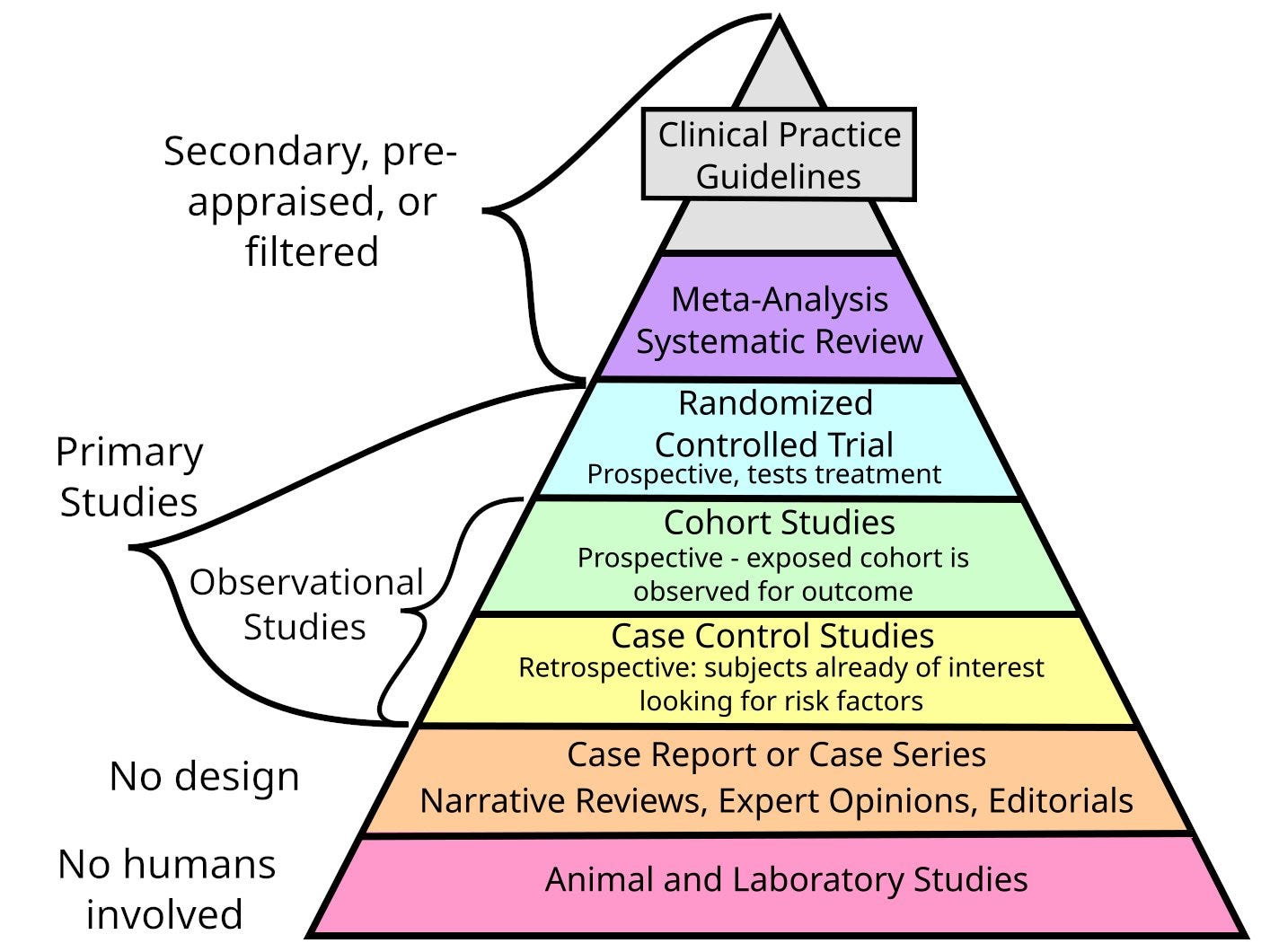

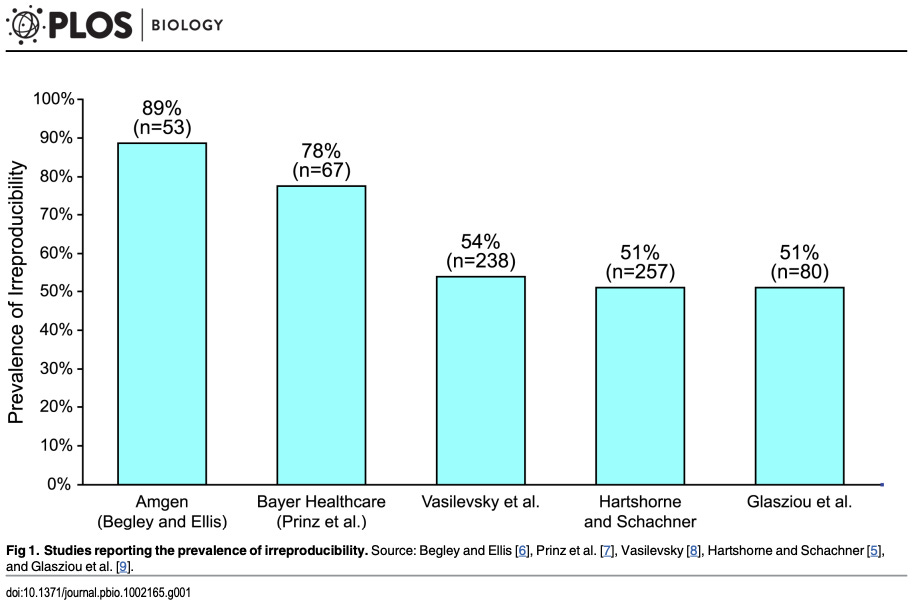

People often point to the reproducibility crisis and lack of rigor in “soft” fields like psychology and the social sciences, but these are also major problems in general, especially in the realm of biology and diet. Even in clinical research, there seems to be an ungodly amount of “zombie studies” circulating among randomized controlled trials (RCTs). The liturgy of modern institutional Science™ is based in large on this corpus of “gold-standard” RCTs, which sits high up in so-called “hierarchy of evidence” upon which public policy guidelines are built.

Atop the hierarchy are the Official Guidelines, which define the ritual practices and sacred doctrines underlying “medicine,” which is practiced and administered by a special caste of Experts, uniquely qualified to understand the esoteric language of the literature. The most reliable forms of knowledge come from meta-analyses and systematic reviews, in which many studies are compiled, analyzed, and distilled into conclusions backed by “the literature” as a whole, not just a single study.

An implicit assumption operating at every level of this pyramid (the word “faith” comes to mind) is that the published literature is reliable, on average and over time. No single study is perfect, and many individual papers may contain critical flaws. But the sum-total of this general effort, the top of The Pyramid, points in the general direction of Truth. Sacred practices such as peer-review serve as key quality control mechanisms that help ensure The Pyramid is sturdy, resting on firm foundation.

And, of course, scientists are careful truth-seeking creatures. Experiments are carefully crafted. The contents of reagents are dutifully documented. Papers diligently composed. Laboratory principals, peer reviewers, and journal editors—those who control which papers make it into The Pyramid—read and review with rapt attention, filtering out sloppy scholarship or poorly controlled experiments.

… right?

Learn more about how institutional science & public health actually work:

Podcast | How Science Really Works: Meta-Research, Publishing, Reproducibility, Peer Review, Funding | John Ioannidis

Article | The Purpose of (Public Health) Institutions

Common Problems of “Diet Science”

In the broad field of how diet effects animal biology and metabolic health, it’s common for the effects of two or more diets to be compared. Very often, the control and experimental diets are distinct in more ways than one, each containing a complex mixture of ingredients. However, the experimental diet is often named as if just one of its salient nutritional features is what matters. Common examples include “high-fat” or “low-fiber” diets. Despite their name, these diets usually differ from control diets beyond their fat and fiber content (although you’d be hard-pressed to know that from reading the papers reporting on them).

What’s worse: the results are usually interpreted and reported as if everything can be explained by the one difference they’ve chosen to talk about. It’s common that the scientists reporting the results don’t even realize all the ways their own experimental diets differ from one another. This leads to conclusions like, “A high-fat diet drives such and such change…” which, in many cases, may be completely wrong.

Preclinical animal studies that use and compare the effects of laboratory diets frequently suffer from one or more of the following problems:

Diets differ beyond what is advertised as the key difference between control and experimental diets. One may have higher fat content, but also contain or lack other consequential ingredients. These differences are often unstated or even unknown to the authors.

Diets with the same name are often inconsistent between studies. Although many, many studies examine the effects of “high-fat” diets, there are often major differences in overall fat content or fatty acid profile from one study to the next, apparent only with close scrutiny or special effort to track down the details. Despite this, the effects are usually interpreted and reported as being driven by “high fat.”

Animal diets do not closely resemble the human diets they’re supposed to model. Many animal studies claim to model “Western” diets. Very often, this is vaguely defined as “high-fat, low-fiber,” or something similar. When you examine the details (if they’re even reported), nutrient profiles can be wildly different from the human diet they claim to model, despite similarity in overall fat content or some other generic parameter.

The authors of the study don’t even know exactly what the diets contain. Yes, you read that right. More than once I have asked scientists on my podcast to describe the experimental diets used in their own work, and they have little idea what they contain beyond “higher in fat” or whatever.

For decades, thousands of preclinical studies have been published that suffer from one or more of these problems. As a result, we’re faced with a huge corpus of poorly controlled studies—studies published in peer-reviewed journals, written with confidence, and filled with jargon—that have nonetheless made it into The Pyramid. Many have been fooled into thinking we know more about the effects of different diets and specific nutrients than we actually do.

The preclinical literature is not the only problem. Entire fields like nutrition epidemiology are filled with junk. The clinical literature has its own problems, such as studies that are under-powered, don’t last enough, and so on. All of this contributes to why exaggerated claims and outright falsehoods make into medical textbooks and guide public policy, from the cultish belief that cholesterol = heart disease to the long-standing myth that high-protein diets are bad for kidney health.

What are experimental animals fed in the lab, and how do scientists model things like the “Western-style” diet? What do terms like this and “high-fat” actually mean, and is this language consistently applied across studies?

Let’s get a sense for how these things are discussed and reported in the scientific literature, and compare it to what we know about the composition of the average human diet in America. We will then use a recently published high-profile diet study, discussed in M&M 240, as an exemplar of scholarship in “diet science,” and why we should not be surprised that we are facing a reproducibility crisis.

Our goal here is not to walk away with any real insight into how dietary composition affects metabolic health. Instead, the purpose of this post is to gain insight into how diet science is conducted in practice—to understand how human social psychology and the incentive structures of institutional Science™ shape how diet science is practiced and published, and why its findings rest on a much shakier foundation than we might like to believe…

Learn more about how medical myths are perpetuated in modern society:

Article | The Cholesterol Cult & Heart Mafia: How the process of science evolves into The Science™ of public policy

Article | Mythology, Medicine & Backwards Nephrology

Article | Scientific Junk Food: A brief dissection of nutritional epidemiology

What do lab animals eat in preclinical diet studies?

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Mind & Matter to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.