Can Psilocybin Cure Alcohol Addiction?

Summary of recent research on psilocybin and the brain circuits involved in alcohol addiction

We’re in the midst of a psychedelic research renaissance, which means we’re going to see more and more high-profile research studies come out — both human clinical studies and basic research in lab animals.

In a new basic research study, scientists dissected the brain circuits and molecular basis for alcohol addiction in rats. They showed that a simple pharmacological intervention, a large dose of psilocybin, can help normalize the behavioral and molecular abnormalities of these rats.

The full study can be read here (if there are paywall issues, use this) and I will summarize some of its key results below, together with commentary on how the results speak to some outstanding questions in the realm of psychedelic medicine.

Background

Alcohol is one of the most widely consumed psychoactive drugs and accounts for an astonishing 5.3% of all deaths annually. A minority of regular alcohol drinkers develop Alcohol Use Disorder, which is defined by heavy alcohol consumption, loss of control over intake, and dependency (i.e. withdrawal after abstinence). While addiction rates for alcohol are lower than for some other drugs (e.g. cocaine, opioids), the extremely large number of people who consume alcohol means a large absolute number of people develop AUD.

People with AUD also tend to have problems in executive functions, such as working memory, decision-making, and attention. There are four approved drugs for AUD but they’re not very good, so the need for treatment innovation here is big.

Before the “War on Drugs” swung into full effect, a fair amount of research was done in the mid-20th century on psychedelics like LSD and psilocybin. There were even hints they could help with addiction. More recently, in the mid-2010s, some small clinical trials provided preliminary evidence that psilocybin-assisted therapy can treat alcoholism. I spoke with a patient who participated in one of these pilot studies, who stopped drinking alcohol after receiving just one psilocybin dose amidst several weeks of psychotherapy. He claims to have been alcohol free ever since, more than six years later.

While these preliminary clinical results are intriguing, they can’t tell us how and why a drug like psilocybin is having its effects. What is it actually doing in the brain? Understanding what’s goin on under the hood requires preclinical research, like the study in rats I’ll be described below.

Alcohol-dependence & cognitive flexibility

Scientists can make rats dependent on alcohol by chronically exposing them to alcohol vapor. They do this for several weeks, confirming their blood alcohol levels along the way. The rats then abstain from alcohol for three weeks. They’re then given behavioral tests and both physical and molecular changes in the brain are measured (i.e. all tests are done in sober rats).

When you test their behavior, the alcohol-dependent rats perform differently compared to control rats. They’re not as quick to adopt new strategies needed to successfully perform an “attentional set-shift task” and they’re more likely go after small, immediate rewards rather than wait for larger, future rewards. So, they have attention problems and are more impulsive. This mirrors what we see in humans with Alcohol Use Disorder.

Receptors & Brain Areas Involved

From past work, scientists knew that alcohol-dependent rats have lower levels of a specific receptor, mGluR2, within the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC). This brain region connects to another area, the Nucleus Accumbens (NAc), which is important for reward learning. If you’re interested in things like drug addiction, this is a brain circuit that comes up a lot.

When they look at these areas in alcohol-dependent rats, they have more connections in medial prefrontal cortex and fewer connections in the Nucleus Accumbens. So, this circuit has been physically altered as a consequence of chronic alcohol intake.

If you inject a virus into this area that increases mGluR2 levels in alcohol-dependent rats, it normalizes some of their behavior: they no longer show cognitive flexibility deficits.

They also show that normal rats, unexposed to alcohol, can show similar cognitive flexibility deficits if you simply reduce mGluR2 levels in this brain region. So, they have evidence linking a specific molecular change in a specific brain region to the cognitive flexibility issues caused by alcohol-dependence.

They do some other experiments related to all this before asking the question: can psilocybin normalize this stuff in alcohol-dependent rats?

Psilocybin Experiments

They had some reason to suspect that psilocybin might be able to restore mGluR2 levels to normal. Psilocybin, as with all classical psychedelics, stimulates the serotonin 2A receptor, which is the “psychedelic receptor” needed for the subjective effects of tryptamines like psilocybin, LSD, and DMT. (If you want more background there, listen to this.)

Without going into detail, they show that psilocybin does seem to restore mGluR2 levels in alcohol-dependent rats. It also reduces their alcohol-seeking behavior.

Importantly, these effects go away if they block psilocybin from stimulating the serotonin 2A receptor using another drug. In other words, the effects they observe for psilocybin require it to stimulate the “psychedelic receptor.”

Psilocybin Dosage

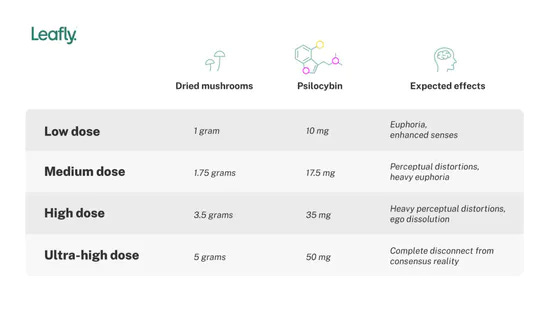

How big were the doses they used? For these experiments, they were using either 1 or 2.5 mg/kg, which means each rat got either 1 or 2.5 milligrams of psilocybin for each kilogram of its body weight. These rats weigh around 275 grams. When you calculate the human equivalent dose, you can’t just scale up the dose linearly due to something called allometric scaling.

If one animal species is 10x the size of another, you would not want to give it 10x the drug dose. That would likely be an overdose, as described in the story at the start of this podcast episode, in which an elephant was given LSD.

When you do the math, the human equivalent dose turns out to be 17.1-42.9 mg of psilocybin. That’s not a microdose. These would be considered full to very large doses. For example, this is how much psilocybin can be found in dried magic mushrooms:

The effects they observed in this study came from fairly large psilocybin doses and required stimulation of the “psychedelic receptor.” It’s possible the same effects could be observed with a lower, sub-threshold dose (a “microdose”), but that wasn’t tested. In either case, fairly clear evidence was found for the involvement of the serotonin 2A receptor, which has been shown elsewhere to be involved in the neuroplastic changes induced by various psychedelic drugs.

Whether the therapeutic mental health effects of psychedelics require a psychedelic trip is an open question in psychedelic science. Some scientists, such as medicinal chemist Dr. David Nichols, think it’s likely that the subjective effects are crucial. Other scientists, such as Dr. David Olson, think the psychedelic and therapeutic effects may be separable and that we will therefore be able to design novel drugs with the same benefits, minus the hallucinogenic effects.

The wonderful thing about the present moment is that we can not only ask, but actually answer, questions like this. With the explosion in psychedelic research, it is likely that we will learn in the coming years the extent to which the powerful subjective effects of psychedelics are causally related to their therapeutic outcomes.

Learn more about this topic:

David Olson: Psychedelics, Psychoplastogens, Microdosing, Mental Health, Brain Chemistry, Creating Novel Drugs | #46 [Audio] [Video]

David Nichols: LSD, DMT, Mescaline, MDMA, Medicinal Chemistry & Psychedelics as Medicine | #33 [Audio] [Video]

Christian Luscher: Drug Addiction, Cocaine, Caffeine, Nicotine, THC, Opioids & the Brain | #40 [Audio] [Video]

Jon Kostakopoulos: Psilocybin Therapy, Alcohol Addiction & Being a Clinical Study Participant | #23 [Audio] [Video]